"With all good wishes, $ax Rohmer"

It has become almost traditional to begin any comments about Sax Rohmer with a discussion of his name. In this case, the piece is about nothing but his name -- or more accurately, "names." He was born of Irish parents on February 15, 1883 and named Arthur Henry Ward. At various times, his mother Margaret told young Arthur that she was descended from an Irish General named Patrick Sarsfield, and about the time of her death in 1901, he adopted Sarsfield as a middle name.Only twenty years old, he submitted "The Mysterious Mummy" to Pearson's Magazine and "The Leopard-Couch" to Chambers's Journal expecting rejection. To his surprise, both were accepted and published in November, 1903 and January 30, 1904 respectively. These early successes were followed by three more titles in Pearson's Magazine: "The Green Spider" in October, 1904, "The Mystery of Marsh Hole" in April, 1905 and "The M'Villin" in December, 1906 -- all five with the byline of "A. Sarsfield Ward."At about this same time he also acquired the rather strange nickname of "Digger" from his Bohemian compatriots, the Oakmead Gang -- a name later used for the narrator of the Crime Magnet stories.In the summer of 1908, the song "Bang Went the Chance of a Lifetime" was published with the byline of Sax Rohmer. R. E. Briney confirms that "This is, so far as I've ever heard, the earliest verified use of the Sax Rohmer byline in print" (Email, July 9. 1998). Later songs such as "Kelly's Gone to Kingdom Come" and "The Camel's Parade," published in 1910, were also attributed to Sax Rohmer.Two years later, in December of 1912, "The Secret of Holm Peel" was published in Cassell's Magazine and attributed to "Sarsfield Ward," but it in unclear whether this was the author's choice or the editor's. At one point he is even said to have considered using "Ward Sars," but he was apparently dissuaded when a friend, Clifford Seyler, "politely enquired how it was to be distinguished from 'Ward's Arse'" (Cay Van Ash, The Rohmer Review No. 11).R. E. Briney discovered four interesting titles published in London between 1908 and 1913 -- all by "Arthur H. Ward." The titles were evocative of Rohmer, particularly the Rohmer of that time. Under the guidance of Dr. R. Watson Councell, Rohmer was quite immersed in theosophy, alchemy and mysticism. Having had success in selling short stories, his central project in 1913 was researching and writing The Romance of Sorcery. In this context, the work of "Arthur H. Ward" must be considered positively Rohmer-like: "The Song of the Flaming Heart" (1908), "The Seven Rays of Development" (1910), "The Threefold Way" (1912) and "Masonic Symbolism and the Mystic Way" (1913). The other "Arthur H. Ward" has yet to be identified, but both Cay Van Ash and Mrs. Rohmer concluded the titles in question were apparently written by someone other than Sax. It is also interesting to note, however, that "Arthur H." apparently stopped writing the very year that "The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu" was first published. (A full discussion of these strange titles is found in "The Mysterious Arthur H. Ward" in The Rohmer Review, No. 12, September, 1974.)Mrs. Rohmer told Cay Van Ash that when she met her future husband in 1905, he introduced himself as "Sax Rohmer," and that he used both "Sax Rohmer" and "Arthur Sarsfield Ward" until about 1913 (The Rohmer Review, No. 14). Why the wavering over name choice? Van Ash felt it was because "on the one hand, he was loath to sacrifice the degree of recognition which 'Arthur Sarsfield Ward' had thus far gained, and, on the other hand, he had devised 'Sax Rohmer' as appropriate to the mystic type of material which he still hoped to write." The issue was decided when the success of Fu-Manchu "gave overwhelming prestige to the pseudonym" (The Rohmer Review, No. 14).While Rohmer discarded the "Henry" in favor of "Sarsfield," others did not. Van Ash notes in Master of Villainy [the biography he co-authored with Mrs. Rohmer] that "as late as 1931 the editors of Liberty Weekly would inform their readers that Sax Rohmer's real name was Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward." R. E. Briney has noted thatRohmer himself didn't help the confusion over his name when he was cited in The Century Cyclopedia of Names and its update The New Century Cyclopedia of Names (by Clarence L. Barnhart and William D. Hasley, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1954, page 3390) with one of his deliberate obfuscations: "He [Rohmer] stated (1930) that his name is not, and never has been, 'Arthur S. Ward'." (Email, July 9, 1998) As late as 1985, the editors at Thorndike Press informed readers of their large type edition of The Mask of Fu Manchu that "Sax Rohmer was the pen name of English author Arthur Wade." While this is the most recent "Wade," there have been quite a few others.

"Egregious errors" aside, what was the origin of the pseudonym,"Sax Rohmer"? The author's own explanation was given in an interview in The New Yorker in 1947.

There are, of course, other Rohmer's. Any search with Alta Vista, Yahoo or the like will turn up thousands of Rohmer's including Eric Rohmer, the French director, authors Richard Rohmer and Harriet Rohmer, as well as numerous people in Germany, an Italian model and a Canadian politician. But where did Arthur Sarsfield Ward come up with "Sax Rohmer"? In the same issue of The Rohmer Review (No. 11) cited above, Douglas A. Rossman suggested an interesting possibility:

There are two notes of interest regarding "Römer Saxe." The author's name is spelled Röhmer (with an umlaut) on the cover and title page of the Dutch title, De Wraak der Goden published in 1936. Literally "The Revenge of the Gods," the book is a translation of The Bat Flies Low. This spelling was undoubtedly the editor's, not the author's. On the other hand, when "A Petition Has Been Filed" was published, the Contents page listed the author as "Romer" without the "h" or the umlaut.Cay Van Ash, who included the above New Yorker quotation in Master of Villainy in 1972, later wrote an article exploring other possible explanations, "The Search for Sax Rohmer," (The Rohmer Review, No.14, July, 1976). Following the New Yorker interview, Rohmer told Van Ash that it was "all nonsense" and was never intended as anything more than "an eye-catching and sonorous combination of syllables." The basic question posed by Cay Van Ash was "had he, as I then supposed him to mean, put the name together simply by trial and error, or had he come upon it ready-made?"The article goes on to explore his reaction to Douglas A. Rossman's letter in issue No. 11 of The Rohmer Review. Van Ash notes that Rohmer went to Europe in 1904, but that "Nothing is known as to what 'Arthur Sarsfield Ward' did after landing at the hook, and it has always seemed strange to me that his journey seemingly provided no settings for subsequent stories." Van Ash concludes with the following theory:

Barring the discovery of some incredibly obscure evidence that Rohmer was, indeed, in Frankfurt in 1904 or thereabouts we'll never know. It might also be noted, however, that one of the characters in "A Mission to Grünzburg" was named "Böhmer." The whole point of Cay Van Ash's speculation or "theorizing" was that Rohmer was mulling over the use of a variation of "Römer Saxe" so having a character named "Böhmer" provides additional circumstantial evidence. Perhaps consciously, perhaps unconsciously, he was getting closer to creating "Sax Rohmer."Two other names actually used by the author must be noted. "About Claire," a rather funny story of a failed seduction, was published under the pseudonym "Potter of Portland Place" in "Holly Leaves" the Christmas Number of the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, Christmas, 1937 (Dated 15 November 1937). Wulfheim, his occult novel, was first printed in 1950 and carried the byline "Michael Furey," Furey being his mother's maiden name.Quite aside from the names Rohmer himself employed, there are the names others have inadvertently given him. In addition to the "Arthur Wade" noted above, Larry Feher has a rebound McKinlay, Stone & Mackenzie edition which misspells his last name as "Rhomer," but this is apparently a unique item. R. E. Briney found a Portuguese translation of The Green Eyes of Bast, "Os Olhos Verdes" with the correct spelling on the cover but "Sax Rohner" with an 'n' on the title page.A. L. Burt, a major source of Rohmer reprints in the United States, had trouble distinguishing "Sax" from the more common American name, "Max." And in Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Terror Time, Dell (1972) "The White Hat" is listed in the contents as by "Sam Rohmer."

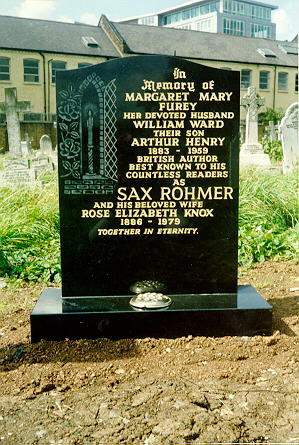

In discussing his many names, it should also be noted that in his flusher days, he developed the habit of signing his name with a dollar sign rather than the letter S, "$ax Rohmer," as in the photo at the top of this page.His grave marker (furnished by Cay Van Ash and a few others) bears both his given name, "Arthur Henry," and the name of the "author known to his countless readers as Sax Rohmer." |

![]()

St. Mary's Cemetery on Harrow Road, London NW10 5NU

Go to The Page of Fu Manchu