Murray Leinster's a Ten(ster), or Deal out the Lincolns to William F. Jenkins

It has long been my belief that science fiction is really the hope of the nation.

I have been saying for years that our real trouble, in the States, is people smoking

mild cigarettes, drinking pale beer, and running after blondes. But I have noticed

that at this convention the brunettes among us have been pursued with real vigah

and enthusiasm—and possibly a little more predacity than the blondes. This

is a heartening thing to witness and it gives me great hope for the future of

the United States because characters like you are real.

[Murray Leinster, from his Guest of Honor Speech at Discon, the 21st World Science Fiction Convention in

1963]

Reading those words now, some forty-six years after he spoke them in

front of the gathered fans and pros of the day, I wonder what he would

have said had Murray Leinster (working name of William Fitzgerald

Jenkins) been the Dean of something other than science fiction. After

all, he wrote mysteries, and westerns, and romances (under the name

Louisa Carter Lee), and had there been the same kind of fandom

surrounding those genres, what might he have told them as Guest of

Honor?

He wasn't Dean

of Westerns, though, or even Romances. He was, for all his work in other areas,

one of US; then, now and forever. Writing for whichever market would pay him wasn't

an indication of hackery, mind you, it was quite a common thing in the days when

almost every conceivable subject had its own pulp magazine.

[i] Robert E. Howard, he of the cowboy hat and mighty-thewed

barbarians, wrote boxing yarns, and even that other Dean of science fiction, Robert

Heinlein, wrote teen confessions. [ii]

He wasn't Dean

of Westerns, though, or even Romances. He was, for all his work in other areas,

one of US; then, now and forever. Writing for whichever market would pay him wasn't

an indication of hackery, mind you, it was quite a common thing in the days when

almost every conceivable subject had its own pulp magazine.

[i] Robert E. Howard, he of the cowboy hat and mighty-thewed

barbarians, wrote boxing yarns, and even that other Dean of science fiction, Robert

Heinlein, wrote teen confessions. [ii]

For Heinlein, though, writing anything other than sf was very much an

aberration, and, in fact, it wasn't until after his death that those few

stories were reprinted under his name. Leinster was a total pro; he

edited his own anthology (Great Stories of Science Fiction,

Random House 1951), unlike RAH who relied on Fred Pohl and Judith

Merrill to pick the stories for Tomorrow, the Stars (Doubleday

1952) [iii]. If there was a market he could figure

out a yarn for, he wrote it and sold it. This strikes me as a handy

thing for a professional writer to be able to do.

William

Fitzgerald Jenkins (aka Murray Leinster and a few others) was born in 1896, on

June 16th, to be exact. I met him three quarters of a century later at a small

convention in downtown Norfolk, Virginia called Dixieland Fancon. Also in attendance

were Donald Wollheim, Wally Wood, Kelly Freas (in 1971, already Virginia's Con

Guest in Residence), and a few others I don't recall. I do remember that Wood

was mostly absent, Wollheim imperious and frighteningly knowledgeable, and Kelly

was, well, Kelly.

[iv]

My

eyes were on Leinster, though. Like most of those attending this never-to-be-repeated

convention, I'd been reading his books and stories pretty much since I'd been

reading sf. His stories had been frequently reprinted in those days, Groff Conklin

alone having presented me with nineteen of them in various anthologies, and he

was no stranger to the other anthologists, major and minor: Wollheim, Derleth,

Bleiler & Dikty, Merrill...he was a favorite of the editors, and therefore

(and/or concurrently/consequently) a favorite of the readers.

How

did this tiny little convention get the Dean? That's easy: he lived just down

the road a piece in Gloucester. It's difficult even now for me to imagine one

of the Giants living in my almost-backyard, but there he was, and remained, until

his death in 1975.

I

was barely even a faan back then. I had attended a number of comic conventions,

but DFC was my first sf con, even if the guy running it was a comic artist rather

than a writer, faan or pro. The idea of meeting and speaking with one of my heroes,

therefore, was more than a little alien to me.

Will,

on the other hand, was an old pro at this. He knew how

not

to embarrass or discourage a fanboy, a skill

I was later to discover was common in most pros, but appallingly lacking in others.

Above all else, Will Jenkins was a gentleman, jokes about brunettes being pursued

with "vigah" notwithstanding.

It's

difficult to pin down his first publication, although Sam Moskowitz, in

Seekers of Tomorrow

(World Publishing, 1967),

makes a good case for it being while Jenkins was barely a teenager. This is confirmed

by Jenkins himself in an interview published in the June 1972 issue of

Literary

Sketches

, a small 'zine published by Mary Lewis Chapman in Williamsburg:

Robert E. Lee is responsible

for my being a writer....[O]ne morning I was in school...[and] they made a very

tragic discovery. They found that it was Robert E. Lee's birthday and nobody had

remembered it. So the Principal, of course, went into a panic and immediately

sent messages to all the teachers that they were to read something to us pupils

about Robert E. Lee and let us write a composition about him...I wrote a composition,

I always loved long words, and I put some nice long words in it....[A] couple

of weeks later the Virginian Pilot [the Norfolk, Virginia daily]

printed my composition....it made quite a stir and a Confederate veteran sent

me a $5 bill.

Jenkins

goes on to say that he took this money and bought the material for a glider:

...I took it down to the [Cape Henry]

lighthouse....I jumped off the top of the lighthouse hill and glided down through

the air and damn near broke my neck....I took a snapshot of myself and the glider

and I sent it, with an account of my achievement, to a magazine called

Fly

—it

was the first aviation magazine in the United States—and they sent me a $5

bill. That was $10 I'd made out of writing.

All

this was in 1908 or '09, when Jenkins was a bright—if foolhardy - twelve

or thirteen. I don't remember exactly what I was doing at age thirteen, but I

can guarantee you it wasn't building and flying gliders, unless they were made

from balsa wood and cost 10¢ down at the Woolworth's.

[v]

He wanted

to become a chemist. This ambition, unfortunately, spiraled down the Porcelain

Facility of Fate when his father went broke and took a job at an auto dealership

in Cleveland (yes, they had such things in 1909). Jenkins, at that time making

$3.50 a week as an office boy, had

"...a frantic

frenzied horror of working for somebody else."

So, out of school and with

no hope whatever of going on to college to become a scientist, he began writing.

At least, he began putting words on paper:

He wanted

to become a chemist. This ambition, unfortunately, spiraled down the Porcelain

Facility of Fate when his father went broke and took a job at an auto dealership

in Cleveland (yes, they had such things in 1909). Jenkins, at that time making

$3.50 a week as an office boy, had

"...a frantic

frenzied horror of working for somebody else."

So, out of school and with

no hope whatever of going on to college to become a scientist, he began writing.

At least, he began putting words on paper:

I started about thirteen—every

night I'd come home from the office and write 1,000 words and I did that everyday

for a year, 360,000 [sic] words, and I tore it all up because it was lousy.

Eventually

he began selling epigrams and filler material to

The Smart Set, one of the most important magazines

of the day, a dozen short pieces for another one of those Lincolns. So, he finally

was a pro writer. How much of one?

"The first year I was writing, and selling my stuff,

I made the magnificent sum of $72."

It

may have been 1913, but $72 at $5 a pop still didn't go very far, so he began

trying his output on the pulps. His editors at

Smart Set

[vi] had something

of a problem with the Jenkins name being soiled by those nasty old nickel and

dime pulps, so they gave him a bit of advice. In Jenkins's words:

One day I was in...the office of this

magazine, and I boasted to them that something that they had returned I had sold

somewhere else. George Jean Nathan—it wasn't fair of him but I was 17 and

I was flattered as hell—he asked me to save my name, Will Jenkins, for

Smart Set

and use a pen name for "inferior"

magazines.

Thus

was born Murray Leinster, a pseudonym concocted from family names. It wasn't too

very long before he discovered that those "inferior" magazines paid Leinster far

better than the more aristocratic

Smart Set

paid

Jenkins, though, so he devoted his energies to pulpdom and let the slicks slide.

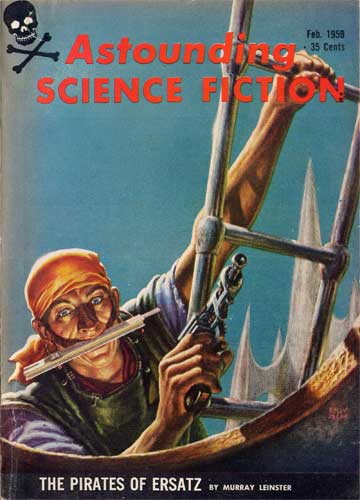

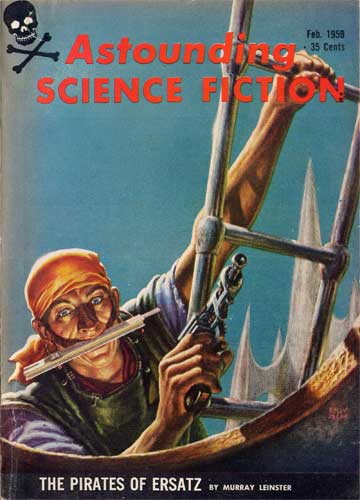

Jenkins

began writing in the 'teens of the 20th Century, and was still writing and getting

awards in his sixties. In 1962, two years and a bit after the appearance of his

Ace novel

The Pirates of Zan

(originally

serialized in

Astounding

as

The Pirates of Ersatz

, which title I like much

better), he was (in the words of Sam Moskowitz)

"...voted one of the six favorite

modern

writers of science fiction..."

[emphasis SaM's]. His last story appeared in a 1967 issue of

Argosy

, and a year later his last article appeared

in

The Writer

.

Jenkins

was a lot like the great jazz saxophonist, Coleman Hawkins. I know that's an odd

comparison, but stick around and you'll get it. The Hawk was a skilled musician

who relied on his chops to make music instead of just memorizing licks. This,

in large part, was a major reason why he was as successful during the post-war

Bop period as he was during the Swing/Big Band era; that, and his clear understanding

of what the Boppers were doing. He liked the renewed energy Bop brought to a moribund

jazz world, and he was able to adapt his playing style to the growing sophistication

of both the listeners and the other musicians. He may never have attained bull-goose

Bophood, but he adapted quite easily and well to fronting small combos.

Given

all that, it would be easy to take the parallel with Hawkins further by cleverly

linking story with song, book with album and so on, but you're faced with that

kind of lit-crit booshwah enough here on the Information Turnpike without my adding

to it. The simple fact is that Jenkins and the Hawk blew damned great stuff, and

a great solo or a great story are all you need to prove yourself to anyone who

matters.

Eventually,

about the time he was 21, his boss (Jenkins was, by this time, a junior bookkeeper

at Prudential) became aware of his extracurricular activities and advised him

that Prudential didn't like its employees to moonlight, so he'd have to stop.

After admitting that he was, in fact, writing, Jenkins stood mute. He was then

taken up on the mountain and shown the kingdoms of the Earth if he would only

bow down. Well, okay, his manager offered him a couple extra bucks a week to spy

on his fellow workers and report any who complained about the company. Fat chance:

"I resigned on the spot and it was worth all the

trouble...when that guy pulled that on me."

He'd

wanted to be a chemist; instead, he became an inventor, maybe the next best thing.

One of his inventions is still used today: a process of front-projecting images

onto a background and actors instead of rear-projection (which prevents the camera

from moving). Perhaps the most famous use of this technique was during the "Dawn

of Man" part of the Kubrick/Clarke film,

2001: A Space Odyssey

.

Most

of his inventions, though, were firmly embedded in the pages of his stories. The

annual award for best alternative history work, The Sidewise, is named for his

story in the June 1934

Astounding

, "Sidewise

in Time," which was later combined with five other stories and issued by Shasta

in 1950 under the same title. The 1934 story isn't the first time stfnal writers

had played with the idea of alternate worlds and timelines—

Wonder Stories

ran John Taine's "The Time Stream"

in the December 1931 issue, and there was an

ad hoc

anthology of speculative essays edited

by one Sir John Collings Squire in 1931 titled

If It Had Happened Otherwise

that included a

piece on the American Civil War by no less a personage than Sir Winston Churchill—but

let's face it, Jenkins/Leinster did it better than they did, and made it look

easy

. That for you, Sir Winston.

That

wasn't his only literary invention, though. In "A Logic Named Joe" in the March

'46 issue of

Astounding

, he basically

rolled up his sleeves and invented the whole damned computer InterWeb thing without

breaking a sweat. That for

you

, Al Gore.

It's

difficult, at some forty-plus years' remove, to recall with any surety just where

I first read a long-time favorite author. In my case, in fact, it's even more

difficult, because most of my reading when I was in my pre-adolescence was in

anthologies, which I saw not necessarily as collections of individual stories

by individual writers, but as massive sources of days and days worth of anonymous

reading, like television I could make up in my own head, if you will. I wasn't

concerned at first with who wrote the words; I was too busy making pictures in

my mind.

That changed

at least a little when I checked Groff Conklin's

Science Fiction Adventures in Mutation

(Vanguard 1955) out of the library

and read a disturbing little story titled "Skag With the Queer Head" by someone

whose name I didn't learn to pronounce correctly until just before meeting him:

our subject, Murray Leinster.

That changed

at least a little when I checked Groff Conklin's

Science Fiction Adventures in Mutation

(Vanguard 1955) out of the library

and read a disturbing little story titled "Skag With the Queer Head" by someone

whose name I didn't learn to pronounce correctly until just before meeting him:

our subject, Murray Leinster.

I

was initially drawn to the author's name because one of my aunts married into

the Murray family, and for a nine year-old kid, it doesn't take much more than

that to make a connection.

But

the story...! Imagine being nine, with a dog of your own, and reading this:

When Deena had her puppies,

she was attended by no less eminent a person than Dr. B. J. Danil, late Wharton

Professor of Experimental Biology at BraddockUniversity. For Deena was no ordinary

dog. Neither she nor her mate, Skag. They were the only two dogs of their kind,

in fact, in the whole world.

I'd

read my share of "mad scientist" yarns, of course, as well as seen them on TV

and in cartoons (remember the Superman cartoon with the giant flying robots? Now,

that

was a mad scientist!), but never before

one in which he wasn't just a foil against which the Hero acted.

Or

perhaps he was, if you accept that in this case the Hero is a genetically altered

Malamute named Skag. For once, in all the stories I'd read up until then, science

wasn't the salvation of anything, but rather the weapon wielded by an uncaring

and unfeeling human against someone who should have been his Best Friend.

Skag

and Deena are the results of experiments in giving animals intelligence on an

almost human level, in this instance by forcing their heads to retain the same

shape as a puppy's, even as it grows larger, thus increasing brain size and intellect.

Nothing unusual about the idea of smart dogs; Simak used it in his City sequence,

and Heinlein used it more than once. The difference here is that Skag and Deena

know what's been done to them, understand the lack of compassion and humaneness

in their tormentor, and are determined that the same things will not be done to

their pups. They act heroically, if impassively, with little of the rage and contempt

the doctor shows them, and in the end are left to themselves to raise their pups

as simply dogs.

Leinster

could have let it go at that, and still have created a pretty intense yarn, but

that's all it would have been—a yarn. He was never content to take the easy

out, though, and if Prof. Danil is a prick, the old geezer who brings his mail

through the Alaskan Winter, Joe Timmins, isn't. He's human to the core, which

means that he has nothing but respect and affection for Skag and Deena, and they

reciprocate.

There

are scenes throughout the story, short as it is, which point up Danil's intentions

towards the pups, as well as his two original subjects, and it becomes very clear

early on that they know exactly what's going on. At one point, as he tries to

take one of the pups from Deena, she grabs his wrist in her teeth; as he pulls

out a gun to kill her, Skag immobilizes his other arm. Then, in a key incident,

the two dogs then argue in their own "language" over what to do next. Deena, protective

of her offspring, wants to simply tear him up. Skag, knowing full well what would

happen if she did, twists Damil's arm until he drops the gun. Skag then carries

it off to the side, then stares at Danil until he slinks away.

I

won't describe the final encounter except to say that what follows is inevitable,

and disturbingly satisfying to a kid who could never stand cruelty to animals.

It stuck in my mind for years after, and upon re-reading it for the first time

in decades, I find it still as disturbing, if not as groundbreaking.

You

can say that about much of Leinster's work, really. He wasn't so much a Cordwainer

Smith as much as he was a Doc Smith. I hasten to add that I

do not

see this as pejorative in the least—not

everyone sits comfortably on the cutting edge, but it don't mean they can't still

be plenty sharp. Leinster never fails to entertain, never makes a wrong move,

never ceases to amaze. His body of work isn't just long and broad, it's got depth.

It isn't self-consciously literary, and he eschewed pretentiousness, I think,

not from any deliberate decision but just because it didn't occur to him that

it might serve the stories he wanted to tell.

I

love my Cordwainerist stories, believe me I do, but I love my Docologist stuff

just as much. I know gourmet writing when I taste it; whether the robust

Provençal

of Bester's "Fondly Fahrenheit" or

the

nouvelle cuisine

of Zelazny's "A Rose

for Ecclesiastes", fine dining is fine dining. On the other hand, sometimes you

just want a plateful of chili, or a steak and baked, and that's where you'll find

Leinster, complete with barbecue tongs and "Kiss the Cook!" apron. You know, comfort

food, but without the pre-processed cheese.

In

the utterly necessary

In Search of Wonder

(Advent 1957) author, editor and critic Damon Knight describes Leinster's writing

in the novel

The Monster From Earth's End

as:

[W]orkmanlike first-reader prose which

has not changed much in the last thirty years....The short, simple sentences carry

the story forward in a sort of spiral fashion: one foot forward, two feet back

to cover the old ground again, then another small advance.

(Knight

didn't really intend the above to be a compliment, but Ghu love him, he was a

critic first and a reader second. Face it, most critics don't read for the same

reason Joe Lunchpail does, they read in order to find ways of describing what

they're reading in cleverly witty ways. The rest of us read to have a good time.)

Leinster's

"carefully pedestrian prose" (Knight's phrase) suits his stories just fine and

dandy. Like Englishman Eric Frank Russell (see last issue), Leinster liked to

posit a puzzle and then solve it right in front of the reader. This made him a

favorite of John Campbell's

Astounding

readership, of course, and he ended up writing more than fifty stories for the

magazine from 1930 (before Campbell was editor) until 1966.

Perhaps

his best known story for

Astounding, if

not his best known period, is "First Contact", which appeared in the May, 1945

issue. In a very real way, this is the archetypal Golden-Age, Campbellian yarn.

Leinster posits a problem, one with far-reaching consequences: two starships meet

in deep space, both of them strangers to the other. No matter how much each might

wish for good relations, neither can take the chance of being followed back to

their home world. What if the Stranger ship were crewed by the alien equivalents

of Professor Moriarty, Genghis Khan, and Evil Lincoln, after all?

Most of

the story is taken up with desperate speculation. How can We trust Them? What

can We do to prove that They can trust Us? Is commerce and communication with

another race worth the risk of annihilation? The debate rages in the human ship,

while the two most important characters—Tommy Dort, a photographer in the

observation staff of the human ship

Llanvabon

,

and an alien crew member Dort calls Buck—get to know each other as well as

circs allow, sending messages back and forth while their respective Captains sweat

it out. One communiqué in response to the

Llanvabon's cautious message of hope for friendship

says it all:

Most of

the story is taken up with desperate speculation. How can We trust Them? What

can We do to prove that They can trust Us? Is commerce and communication with

another race worth the risk of annihilation? The debate rages in the human ship,

while the two most important characters—Tommy Dort, a photographer in the

observation staff of the human ship

Llanvabon

,

and an alien crew member Dort calls Buck—get to know each other as well as

circs allow, sending messages back and forth while their respective Captains sweat

it out. One communiqué in response to the

Llanvabon's cautious message of hope for friendship

says it all:

Tommy said dispassionately: "He says,

sir, 'That is all very well but is there any way for us to let each other go home

alive? I would be happy to hear of such a way if you can contrive one. At the

moment it seems to me that one of us must be killed.'"

Boo

-yah. Now,

that's

a problem to be solved. The solution

is a clever one, as befits a self-educated inventor. I won't reveal it here, for

obvious reasons. I will say, though, that Jenkins/Leinster is at his best in this

story, "workmanlike first-reader prose" and all. Not only is there plenty of shrewdness

to go around twice or thrice, not only are the characters and situations easy

to comprehend and identify with, but the author weaves his trademark wit and humor

throughout. The relationship that grows between Tommy Dort and "Buck" is one of

sympathy and mutual respect and interest; we could ask little more of our real

First Contact than to have two such somewhere in the middle of it all.

But

where did the writer we in the stfnal community came to know and love as Murray

Leinster get

his

start? What was his first

undeniably science-fictional story?

Let

me give you a little more background first. Bear with me, I won't keep you waiting

long. A long time ago, there was a weekly magazine called

The Argosy

. It published a lot of material -

some 90k words per issue—and it was one of the most popular of the dime fiction

periodicals. Leinster had been selling them what the editor (one Matthew White,

Jr.; Leinster described him as

"...a little man

with snow white whiskers and a slight lisp..."

) called "Happy Village Stories,"

sentimental yarns much along the lines of those sappy paintings done by Thomas

Kincaid, the

soi-disant

"Painter of Light."

As

you might imagine, Leinster got a little tired of writing these, even though White

bought all he could crank out. Finally, he turned one in with a note saying that

he was done with them:

...I finished a story

and sent it to him and said, "No more Happy Village stories, for the time being,

I'm writing a story that I call the RUNAWAY SKYSCRAPER...the opening sentence

is—'The whole thing began when the clock on the Metropolitan Tower began

to run backwards!'"...I got, by return mail, a letter—"Dear Murray, when

you finish that story about the Runaway Skyscraper, let me see it at once." And

I had to write the darn thing to keep him from finding out I was a liar.

The

darn thing was published in the February 22, 1919 issue of

The Argosy and Railroad Man's Magazine

, and

has seen few reprintings since. It was not, however his first sf/fantasy story

to see print, as his "Oh, Aladdin!" ran not quite six weeks earlier.

It

took a few years for him to get around to writing sf, in spite of the fact that

he'd been reading it for a long time. It wasn't just because he was selling plenty

of other things, although that was certainly a factor. No, it was something else

entirely.

I've

been reading sf and hanging with my stfnal peeps for more than forty years now,

and I've noticed that there are two basic types of writers, no matter what the

genre. There are those who read everything voraciously, constantly, and to the

exclusion of practically all else, then wake up one day and say "Hell,

I

can write this stuff. What's Jules Ursula

C. J. 'Doc' Heinellison del Rey van Tucker got that I

don't

?" and then they start cranking them out.

Then

there are those who read everything voraciously, constantly, and to the exclusion

of practically all else, then wake up one day and say, "Boy, I wish I could write

like Cordwainer L. Sprague Isaac Poul O'Spinrad Aldiss, but I just don't know..."

Believe

it or not, Will Jenkins was in that second category, at least at first:

I had been reading science fiction

and I loved it, but I didn't think I was smart enough to write it. But...when

I had to do it, I got away with it....I was very much surprised to find that I

could write this type that I had admired so much and loved so much.

Well,

he made up for any lost time, believe me. Just look at the biblio at the end of

this darn thing.

William

Fitzgerald Jenkins's career as Murray Leinster lasted a long, long time. He was

active, if not writing, until his death in 1975, just short of eighty years after

he was born. He was a dyed-in-the-wool Southern Gentleman, generous with his time

and advice to younger authors. In his recent (as I write this) collection of autobiographical

sketches,

Other Spaces, Other Times

(Nonstop

Press 2009), Robert Silverberg—no slouch himself when it comes to career

spans—writes of meeting Jenkins in the

Astounding

offices in 1956. Jenkins was already

sixty, Silverberg a svelte twenty-one (and three years away from being able to

purchase Fiorello La Guardia's old digs), and was there to give John Campbell

a new story, titled "Sourdough."

Campbell

read the fourteen page manuscript then and there, as was his habit, then said

(in Silverberg's words),

"Something's wrong with

the ending of this, but I'm not sure what. Will, would you mind taking a look?"

and passed the 'script to the elder writer. Silverberg writes:

Jenkins, the cagy old pro, skimmed swiftly through the story, nodded,

indicated page twelve. "I see the problem," he said—to Campbell,

not to me. And offered a dazzling rewrite suggestion, with which

Campbell concurred. John pointed to the typewriter on his secretary's

desk and instructed me to sit down and write a couple of new paragraphs

right on the spot....Campbell bought the story ten minutes later.

Nor

was Silverberg the only famous writer in the field to benefit from Jenkinsian

counsel, as none other than that other Dean of Science Fiction, Robert Heinlein,

wrote in a letter to his agent dated July 28, 1959 and subsequently published

in

Grumbles From the Grave

(Del Rey 1989):

...I have always worked on the theory that there is always a market

somewhere for a good story—a notion that Will Jenkins pounded into

my head many years ago.

Heinlein

mentions this elsewhere as well. In his essay "On the Writing of Speculative Fiction"

written for the 1947 Fantasy Press non-fiction anthology

Of Worlds Beyond

(edited by Lloyd Arthur Eschbach),

he writes:

Several years ago Will F. Jenkins said

to me, "I'll let you in on a little secret, Bob.

Any

story—science fiction, or otherwise—if

it is well-written, can be sold to the slicks." Will himself has proved this....

Jenkins

wrote a lot in his six-decade career, impressing even the normally sober and dignified

L. Sprague de Camp. In his

Science Fiction Handbook

(Hermitage 1953), he wrote:

He has been writing fiction ever since

1915, his total number of stories reaching the staggering total of over 1,300,

and he is the author of over thirty books....Mr. Jenkins has written almost every

kind of copy including westerns, detective stories, adventure stories, love stories,

comic-book continuity, reports on scientific research, technical articles, and

radio and television scripts.

While

I'm quoting the famous in reference to our subject, let me add one more. I mentioned

up at the top there that Jenkins/Leinster was a favorite of the anthologists,

and this is true. He remains one of the most reprinted classic authors almost

thirty-five years after his death. In his headnote to the aforementioned story

"Skag With the Queer Head" reprinted in Science Fiction Adventures in Mutation

[vii] (Vanguard 1955), editor Groff Conklin wrote:

The Leinster-Sturgeon race in the Conklin anthologies is now a "draw"; each man has appeared in all

but one [viii] of my sixteen

published or about-to-be-published collections. It is true that in two anthologies

Leinster turned up under his own name, Will Jenkins, but this does not spoil the

record.

All

told, Jenkins/Leinster would appear in nineteen of Conklin's forty-one anthologies,

to Sturgeon's twenty-three, a very close second. Other editors would reprint his

stories over and over, right up until the present. As the first Dean of the genre,

he helped blaze the trail for all the other Golden-Age writers, and most of those

who came later. Allen Steele, Catherine Asaro, the late Charles Sheffield, any

who still write hard-science fiction, who pose and then solve sweeping problems

that threaten our tiny little system, owe much to William Fitzgerald Jenkins,

our own Murray Leinster.

[i] Including, believe it or not, plutocracy. There was a magazine,

titled The Wizard, which featured an ongoing

series of stories about one Cash Gorman. If that's not a blatant attempt to combine

an MBA with barbarian bad-assness, I don't know what is.

[ii] Now, that's a concept to boggle the

psyche, but I'll take it further: RAH owned a lava lamp, and wanted a

bigger one.

[iii] I wrote about these two books way back in

December of 2004 in SF Chronicle #254 under the subtitle "The

Deans' List(s).

[iv] More on this most immaculately talented artist next time.

[v]I once jumped out of my treehouse with a toy

parachute, but I was never dumb enough to tell anybody about it, much

less take pictures. I wouldn't have minded the $5, though.

[vi] H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan. I told

you Smart Set was important.

[vii] Groff Conklin was certainly the most important anthologist

of the 1950s and '60s, assembling forty-one anthos (among other projects) from

1946 until his death in 1968.

[viii] The antho Conklin speaks of in which

neither Jenkins nor Leinster appear was 1954's Science Fiction

Thinking Machines , published by Vanguard. It's funny; you'd have

thought it would have been The Supernatural Reader or Science

Fiction Terror Tales , fantasy and horror not being the author's

specialty, but there it is.

William F. Jenkins/Murray Leinster Bibliography

(As

usual, this bibliography is for initial appearances only, and necessarily concentrates

primarily on his sf and fantasy.As Leinster/Jenkins was one of the most prolific

authors in the field, a complete biblio is inevitably impossible — there

are those far more assiduous than I who have worked for years to assemble one,

I promise you, and they're still not finished.In any case, such a project would

be far larger than even JBU would allow me, so rest assured that there's still

plenty of work for you to do by sending me additions and/or corrections.I want

to thank Phil Stephensen-Payne once again for his help with the below, as well

as by William Contento and Stephen Miller and their invaluable Science

Fiction, Fantasy, & Weird Fiction Magazine Index: 1890-2007. If you're at all serious about studying

or collecting classic sf and fantasy, you could do far worse than to purchase

their index.Google them for details.

(In the listings below, text in square

brackets indicates a series. Books listed are for the first edition of each format

only.)

Short Fiction

"My Neighbor" — February 1916 Smart Set

"Grooves" — October 12, 1918 All-Story Weekly

"Oh, Aladdin!" — January 11, 1919 Argosy

"The Runaway Skyscraper" — February 22, 1919 Argosy and Railroad Man's Magazine

"Footprints in the Snow" — June 7, 1919 All-Story Weekly

"A Thousand Degrees Below Zero" — July 15 1919 Thrill Book [Davis & Gerrold]

"The Silver Menace" — serial, September 1 & 15, 1919 Thrill Book [Davis & Gerrold]

"Juju" — October 15, 1919 Thrill Book

"The Mad Planet" — June 12, 1920 Argosy [Burl]

"The Red Dust" — April 2, 1921 Argosy All-Story Weekly [Burl]

"Nerve" — June 4, 1921 Argosy All-Story Weekly

"The Seventh Bullet" — July 1922 Ace High

"The Street of Magnificent Dreams"— August 5, 1922 Argosy All-Story Weekly

"The Man Who Went Black" — October 1, 1922 Ace-High (as by Will F. Jenkins, also August 1931 Jungle Stories as by Will T. Jenkins, possibly a typo)

"The Oldest Story in the World" — August 1925 Weird Tales

"The Man Who Didn't Shoot" — June 1926 Danger Trail

"Sword of Kings" — July 1927 Frontier Stories

"The Strange People" — serial, March-May 1928 Weird Tales

"The Blonde and the Outlaw" — serial, February-May 1929 Triple-X Magazine

"The Darkness on Fifth Avenue" — November 30 1929 Argosy [Hines]

"The City of the Blind" — December 28 1929 Argosy [Hines]

"The Murderer" — January 1930 Weird Tales

"Tanks" — January 1930 Astounding

"The Storm that Had to be Stopped" — March 1, 1930 Argosy [Hines]

"Murder Madness" — serial, May-August 1930 Astounding

"The Man Who Put Out the Sky" — June 14, 1930 Argosy [Hines]

"The Fifth-Dimension Catapult"— January 1931 Astounding [Tommy Reames]

"The Power Planet"— June 1931 Amazing

"The Two Gun Kid" — serial, July-October 1931 Triple-X Western

"Morale" — December 1931 Astounding

"The Racketeer Ray" — February 1932 Amazing

"Politics" — June 1932 Amazing

"The Fifth-Dimension Tube" — January 1933 Astounding [Tommy Reames]

"The Monsters" — January 1933 Weird Tales

"Borneo Devils" — February 1933 Amazing

"Invasion"— March 1933 Astounding

"The Body in the Taxi" — October 1933 Black Bat Detective Mysteries [The Black Bat]

"Beyond the Sphinxes' Cave"— November 1933 Astounding

"The Trouble on the Dude Ranch" — November 1933 Black Bat Detective Mysteries (as by Will F. Jenkins)

"The Coney Island Murder" — November 1933 Black Bat Detective Mysteries [The Black Bat]

"The Hollywood Murders" — December 1933 Black Bat Detective Mysteries [The Black Bat]

"Murder at the First Night" — January 1934 Black Bat Detective Mysteries [The Black Bat]

"The Maniac Murders" — February 1934 Black Bat Detective Mysteries [The Black Bat]

"The Warehouse Murders" — April 1934 Black Bat Detective Mysteries [The Black Bat]

"Sidewise in Time" — June 1934 Astounding

"The Mole Pirate" — November 1934 Astounding

"Conquest of the Stars" — March 1935 Astounding

"Proxima Centauri" — March 1935 Astounding (aka "Conquest of the Stars")

"The Morrison Monument" — August 10, 1935 Argosy

"The Challenge from Beyond" — September 1935 Fantasy Magazine (this was a five-part round-robin story; the other authors, in

order, were Stanley G. Weinbaum, Donald Wandrei, E. E. "Doc" Smith, and Harl Vincent [pseud. of Harold Vincent Schoepflin])

"The Fourth-Dimensional Demonstrator" — December 1935 Astounding

"The Incredible Invasion" — serial, August-December 1936 Astounding

"Side Bet" — July 31, 1937 Colliers (as by Will F. Jenkins)

"No More Walls" — June 26, 1937 Colliers (as by Will F. Jenkins, aka "Wall of Fear")

"Swords and Mongols" — April 1939 Golden Fleece

"Friends" — December 25, 1940 Short Stories

"The Wabbler" — October 1942 Astounding

"Double for Murder" — November 1942 Strange Detective Mysteries

"Four Little Ships" — November 1942 Astounding

"'...If You Can Get It'" — November 1943 Astounding

"Plague" — February 1944 Astounding

"Trog" — June 1944 Astounding

"The Eternal Now" — Fall 1944 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"De Profundis" — Winter 1945 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"First Contact" — May 1945 Astounding

"The Ethical Equations" — June 1945 Astounding

"Things Pass By" — Summer 1945 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Tight Place" — July 1945 Astounding

"Pipeline to Pluto" — August 1945 Astounding

"The Power" — September 1945 Astounding

"Incident on Calypso" — Fall 1945 Startling Stories

"Interference" — October 1945 Astounding

"The Disciplinary Circuit" — Winter 1946 Thrilling Wonder Stories [Kim Rendell]

"The Plants" — January 1946 Astounding

"Adapter" — March 1946 Astounding

"A Logic Named Joe" — March 1946 Astounding (as by Will F. Jenkins)

"Like Dups" — Spring 1946 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Dead City" — Summer 1946 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Pocket Universes" — Fall 1946 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The End" — December 1946 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Friends" — January 1947 Startling

"Time to Die — January 1947 Astounding

"The Manless Worlds — February 1947 Thrilling Wonder Stories [Kim Rendell]

"The Laws of Chance — March 1947 Startling Stories

"Skit-Tree Planet" — April 1947 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Gregory Circle" — April 1947 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by William Fitzgerald) [Bud Gregory]

"From Beyond the Stars" — June 1947 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by Will F. Jenkins)

"The Boomerang Circuit" — June 1947 Thrilling Wonder Stories [Kim Rendell]

"The Nameless Something" — June 1947 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by William Fitzgerald) [Bud Gregory]

"Propagandist" — August 1947 Astounding

"The Deadly Dust" — August 1947 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by William Fitzgerald) [Bud Gregory]

"The Day of the Deepies" — October 1947 Famous Fantastic Mysteries

"The Man in the Iron Cap" — November 1947 Startling Stories

"Planet of Sand" — February 1948 Famous Fantastic Mysteries

"The Seven Temporary Moons" — February 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by William Fitzgerald) [Bud Gregory]

"West Wind" — March 1948 Astounding

"The Strange Case of John Kingman" — May 1948 Astounding

"Space-Can" — June 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Night Before the End of the World" — August 1948 Famous Fantastic Mysteries

"The Devil of East Lupton, Vermont" — August 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by William Fitzgerald)

"Regulations" — August 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Ghost Planet" — December 1948 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Story of Rod Cantrell" — January 1949 Startling Stories [Rod Cantrell]

"Assignment on Pasik" — February 1949 Thrilling Wonder Stories (as by William Fitzgerald)

"The Black Galaxy" — March 1949 Startling Stories [Rod Cantrell]

"The Lost Race" — April 1949 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Life-Work of Professor Muntz" — June 1949 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Fury from Lilliput" — August 1949 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Doomsday Deferred" — September 24, 1949 The Saturday Evening Post (as by Will F. Jenkins, aka "The Soldado Ant")

"The Queen's Astrologer" — October 1949 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Other World" — November 1949 Startling Stories

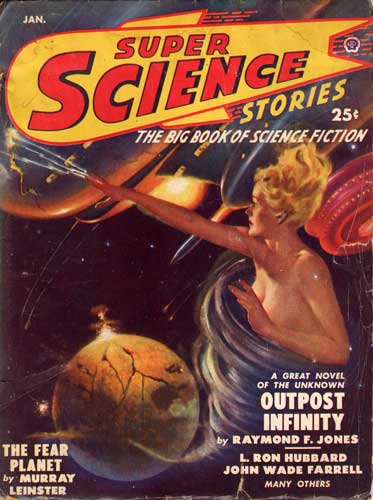

"This Star Shall Be Free" — November 1949 Super Science Stories

"Cure for a Ylith" — November 1949 Startling Stories (as by William Fitzgerald)

"The Lonely Planet" — December 1949 Thrilling Wonder Stories

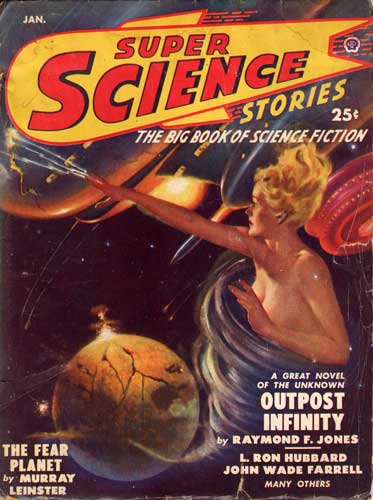

"The Fear Planet" — January 1950 Super Science Stories

"Planet of the Small Men" — April 1950 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"Nobody Saw the Ship" — May/June 1950 Future

"Be Young Again!" — July/August 1950 Future

"Journey to Barkut" — serial (incomplete, the magazine folded before finishing), October 1950 (#7) and January 1951 (#8) Fantasy Book; the complete version appeared in the January 1952 Startling

"Historical Note" — February 1951 Astounding

"The Other Now" — March 1951 Galaxy

"Skag with the Queer Head" — August 1951 Marvel Science Fiction

"If You Was a Moklin" — September 1951 Galaxy

"Keyhole" — December 1951 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Gadget Had a Ghost" — June 1952 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Plants" — June 1952 Great American Science Fiction (Aust.)

"Conquest of the Stars" — July 1951 Science Fiction (Aust., aka "Proxima Centauri")

"The Middle of the Week After Next" — August 1952 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Barrier" — September 1952 Space Science Fiction

"The Unknown" — November 1952 American Science Fiction (Aust., aka "Fury from Lilliput")

"The Journey" — in Star Science Fiction Stories, ed. Frederik Pohl, Ballantine 16, 1953

"Overdrive" — January 1953 Startling Stories

"The Invaders" — April/May 1953 Amazing

"The Sentimentalists" — April 1953 Galaxy

"Dear Charles" — May 1953 Fantastic Story Magazine (as by William Fitzgerald)

"The Castaway" — June 1953 Universe

"Nightmare Planet" — June 1953 Science Fiction Plus [Burl]

"The Ship Was a Robot" — June 1953 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Jezebel" — October 1953 Startling Stories

"The Trans-Human" — December 1953 Science Fiction Plus

"Second Landing" — Winter 1954 Thrilling Wonder Stories [Canis Venatici]

"Fugitive from Space" — May 1954 Amazing

"The Amateur Alchemist" — Fall 1954 Thrilling Wonder Stories

"The Psionic Mousetrap" — March 1955 Amazing

"Sam, This Is You" — May 1955 Galaxy

"White Spot" — Summer 1955 Startling Stories

"Honeymoon on Dlecka" — July 1955 Fantastic Universe

"Scrimshaw" — September 1955 Astounding

"Sand Doom" — December 1955 Astounding [Colonial Survey]

"Exploration Team" — March 1956 Astounding [Colonial Survey]

"Critical Difference" — July 1956 Astounding [Colonial Survey]

"The Swamp Was Upside Down" — September 1956 Astounding [Colonial Survey]

"Women's Work" — November 1956 Science Fiction Stories

"Anthropological Note" — April 1957 F&SF

"Ribbon in the Sky" — June 1957 Astounding [Calhoun/Med Service]

"Med Service" — August 1957 Astounding (Calhoun [Med Service])

"The Grandfathers' War" — October 1957 Astounding [Calhoun/Med Service]

"The Machine That Saved the World" — December 1957 Amazing

"Short History of World War Three" — January 1958 Astounding

"The Strange Invasion" — April 1958 Satellite

"The Pirates of Ersatz" — serial, February-April 1959 Astounding

"The Aliens" — August 1959 Astounding

"Long Ago, Far Away" — September 1959 Amazing

"A Matter of Importance" — September 1959 Astounding

"Rogue Star" — in Twists in Time, Avon T389, 1960 (coll., 7 stories)

"Attention Saint Patrick" — January 1960 Astounding

"The Leader" — February 1960 Astounding

"Tyrants Need to Be Loved" — February 1960 Fantastic

"The Ambulance Made Two Trips" — April 1960 Astounding

"The Corianis Disaster" — May 1960 Science Fiction Stories

"The Covenant" — July 1960 Fantastic (as in the case of "Challenge From Beyond", this was part four of a five-part round-robin, but is complete in one issue.The other authors were, in order, Poul Anderson, Isaac Asimov, Robert Sheckley, and Robert Bloch.In the second volume of his two-volume autobiography,

In Memory Yet Green/In Joy Still Felt [Doubleday 1979-80], Asimov says "I think any one of the five authors could have written a better story if he had done it all himself.")

"Doctor" — February 1961 Galaxy

"Pariah Planet" — July 1961 Amazing [Calhoun/Med Service]

"The Case of the Homicidal Robots" — August 1961 F&SF

"Imbalance" — December 1962 Fantastic

"Third Planet" — April 1963 Worlds of Tomorrow

"The Hate Disease" — August 1963 Analog [Calhoun/Med Service]

"Manners and Customs of the Thrid" — September 1963 If

"Med Ship Man" — October 1963 Galaxy [Calhoun/Med Service]

"Lord of the Uffts" — February 1964 Worlds of Tomorrow

"Spaceman" — March, April 1964 Analog

"Plague on Kryder II" — December 1964 Analog [Calhoun/Med Service]

"Killer Ship" — October, December 1965 Amazing

"A Planet Like Heaven" — January 1966 If

"Stopover in Space" — June, August 1966 Amazing

"Quarantine World" — November 1966 Analog [Calhoun/Med Service]

"The Tiger" — March 1967 Argosy

"On a Hot Summer Night in a Place Far Away" — in Future Earths, ed. Mike Resnick and Gardner Dozois

"The Great Catastrophe" and "To All Fat Policemen" — in First Contacts, ed.

Articles

Why I Use a Pen Name — October/November 1934 Fantasy Magazine

Author, Author — Spring 1949 The Fanscient (as by Will F. Jenkins)

Guest Editorial — September 1952 Startling Stories

Where Are Those Space-Ships? — August 1953 Startling Stories

To Build a Robot Brain — April 1954 Astounding

Labor of Love — January 1956 Astounding

Applied Science Fiction — November 1967 Analog

Writing Science Fiction Today — May 1968 The Writer

Novels and Collections

Murder Madness — Brewer Warren 1931

Murder of the U.S.A. — Crown 1946; Newsstand 141, 1950 (as by Will F. Jenkins)

The Last Space Ship — Fredrick Fell, Inc. 1949; Galaxy SF Novel 25, 1955 (coll. 3 stories) [Kim Rendell]

Fight For Life — Crestwood Prize Science Fiction Novels 10, 1949 (digest-sized, orig. as "The Laws of Chance")

The Lonely Planet — Whitman 1950

Sidewise in Time — Shasta 1950 (coll. 6 stories)

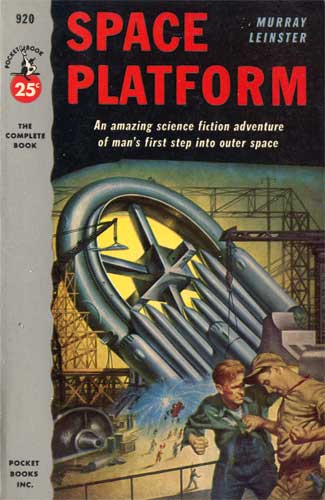

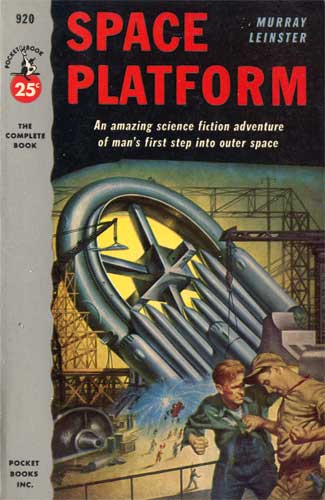

Space Platform — Shasta 1953; Pocket Books 920, 1953 [Joe Kenmore]

Space Tug — Shasta 1953; Pocket Books 1037, 1955 [Joe Kenmore]

The Black Galaxy — Galaxy SF Novel 20, 1954 (orig. in the March 1949 Startling)

The Forgotten Planet — Gnome Press 1954; Ace D-146, 1956 (coll. 3 stories, bound with Lee Correy's Contraband Rocket) [Burl]

Gateway to Elsewhere — Ace D-53, 1954 (orig. as "Journey to Barkut" in the January 1952 Startling, bound with A. E. van Vogt's The Weapon Shops of Isher)

The Brain Stealers — Ace D-79, 1954 (orig. as "The Man in the Iron Cap" in the November 1947 Startling, bound with Francis Rufus Bellamy's Atta)

Operation: Outer Space — Fantasy Press 1954; Golden SF Library, 1957 The Other Side of Here — Ace D-94, 1955 (expanded from "The Incredible Invasion", orig. serialized in the August-December 1936 Astounding, bound with A. E. van Vogt's One Against Eternity)

Colonial Survey — Gnome Press 1956 (fix-up of 4 stories); Avon T202, 1957 (as The Planet Explorer)

City on the Moon — Avalon 1957; Ace D-277, 1958 (bound with Men on the Moon, ed. Donald A. Wollheim) [Joe Kenmore]

Out of This World — Avalon 1958 (coll. 3 stories, all as by William Fitzgerald) [Bud Gregory]

War With the Gizmos — Gold Medal s751, 1958 (orig. in the April 1958 Satellite as "The Strange Invasion")

Four From Planet Five — Gold Medal s937, 1959 (orig. as "Long Ago, Far Away" in the September 1959 Amazing)

The Monster From Earth's End — Gold Medal s832, 1959

Monsters and Such — Avon T345, 1959 (coll. 7 stories)

The Mutant Weapon — Ace D-403, 1959 (bound with his The Pirates of Zan, orig. as "Med Service" in the August 1957 Astounding) [Med Service]

The Pirates of Zan — Ace D-403, 1959 (orig. serialized as "The Pirates of Ersatz", bound with his The Mutant Weapon in the February-April 1959 Astounding) [Med Service]

The Aliens — Berkley G-410, 1960 (coll. 5 stories)

Men Into Space — Berkley G461, 1960 (TV tie-in)

Twists in Time — Avon T389, 1960 (coll. 7 stories)

Creatures of the Abyss — Berkley G-549, 1961 (aka The Listeners)

This World is Taboo — Ace D525, 1961 (orig. as "Pariah Planet" in the July 1961 Amazing) [Med Service]

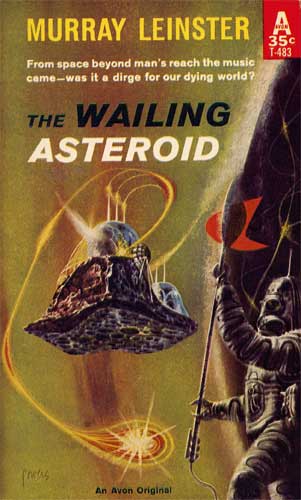

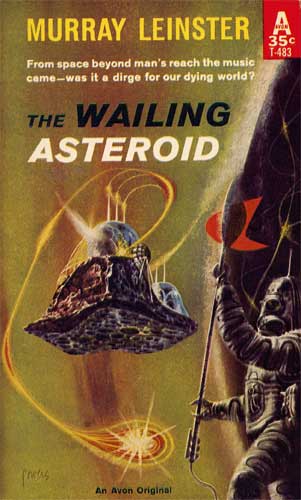

The Wailing Asteroid — Avon T483, 1961

Operation Terror — Berkley F694, 1962

Talents, Incorporated — Avon G1120, 1962

Doctor to the Stars — Pyramid F987, 1964 (coll. 3 stories) [Med Service]

The Greks Bring Gifts — Macfadden 50-224, 1964

Invaders of Space — Berkley F1022, 1964

Time Tunnel — Pyramid R1043, 1964 (TV tie-in)

The Other Side of Nowhere — Berkley F918, 1964 (orig. serialized as "Spaceman" in the March-April 1964 Analog)

The Duplicators — Ace F-275, 1964 (orig. as "Lord of the Uffts" in the February 1964 Worlds of Tomorrow, bound with Philip E. High's No Truce With Terra)

Get Off My World! — Belmont B50-676, 1966 (coll. 3 stories)

Space Captain — Ace M-135, 1966 (orig. serialized as Killer Ship in the October-December 1965 Amazing, bound with Philip E. High's The Mad Metropolis)

Tunnel Through Time — Westminster 1966

Checkpoint Lambda — Berkley F1263, 1966 (orig. serialized as Stopover in Space in the June-August 1966 Amazing)

Miners in the Sky — Avon G1310, 1967

S.O.S. From Three Worlds — Ace G-647, 1967 (coll. 3 stories) [Med Service]

The Space Gypsies — Avon G1318, 1967

The Time Tunnel — Pyramid R1522, 1967 (TV tie-in, not the same as earlier entry)

Timeslip! — Pyramid R1680, 1967 (TV tie-in)

A Murray Leinster Omnibus — Sidgwick Jackson 1968 (UK, reprints Operation Terror, Checkpoint Lambda, and Invaders of Space)

Land of the Giants — Pyramid X1846, 1968 (TV tie-in)

Land of the Giants 2: The Hot Spot — Pyramid 1921, 1969 (TV tie-in)

Land of the Giants 3: Unknown Danger — Pyramid 2105, 1969 (TV tie-in)

The Best of Murray Leinster — ed. Brian Davis, Corgi , 1976 (UK, coll. 10 stories, not connected with the following entry)

The Best of Murray Leinster — ed. John J. Pierce, Ballantine/del Rey , 1978 (coll. 13 stories)

The Med Series — Ace , 1983 (aka Quarantine World, coll. 5 stories) [Med Service] First Contacts: The Essential Murray Leinster — ed. Joe Rico, NESFA 1998 (coll. 24 stories)

Med Ship — ed. Eric Flint and Guy Gordon, Baen , 2002 (coll. 8 stories) [Med Service]

Planets of Adventure — ed. Eric Flint and Guy Gordon, Baen , 2003 (coll. 12 stories)

A Logic Named Joe — ed. Eric Flint and Guy Gordon, Baen , 2005 (coll. 6 stories)

The Runaway Skyscraper and Other Tales from the Pulps — Wildside Press 2007 (coll. 8 stories)

Anthology

Great Stories of Science Fiction — Random House 1951

Non-SF

Her Desert Lover: A Love Story — Chelsea House 1925 (romance, as by Louisa Carter Lee)

Her Other Husband: A Love Story — Chelsea House 1929 (romance, possibly as by Louisa Carter Lee)

Scalps: A Murder Mystery — Brewer & Warren 1930 (mystery, aka Wings of Chance)

Love and Betty: A Love Story — Chelsea House 1931 (romance, as by Louisa Carter Lee)

Murder Will Out — John Hamilton 1932 (mystery)

The Gamblin' Kid — A. L. Burt, 1933; (western, as by Will Jenkins)

Mexican Trail — A. L. Burt, 1933 (western, as by Will Jenkins)

Sword of Kings — John Long 1933 (adventure, orig. in the July 1927 Frontier Stories)

Fighting Horse Valley — King 1934 (western, as by Will Jenkins); Quarter Books 20, 1948 (as by Murray Leinster, aka Texas Gunslinger)

Outlaw Sheriff — King 1934; The West in Action 1, 1948 (digest-size, western)

Kid Deputy — Alfred H. King 1934; The West in Action 3, 1948 (digest-size, western, as by Will F. Jenkins, orig. serialized in the February-April 1928 Triple-X Western)

No Clues — Wright & Brown 1935 (mystery, as by Will F. Jenkins)

Murder in the Family — John Hamilton 1935 (mystery, as by Will F. Jenkins, orig. in the April 1934 Complete Detective Novels)

Black Sheep - Julian Messer 1936 (western, as Will F. Jenkins, aka Texas Gun-Law)

Guns for Achin — Wright & Brown, 1936 (western, as Will F. Jenkins, orig. in the November 1936 Smashing Novels)

The Man Who Feared — Gateway 1942 (mystery, as by Will F. Jenkins); Hangman's House 4, 195? (digest-size, as by Will F. Jenkins)

The Blonde and the Outlaw — Bell Novels 1945 (western, orig. serialized in the February-May 1929 Triple-X Magazine, aka Outlaw Guns and Wanted - Dead or Alive)

Cowgirl Fury — Bell Novels 1946 (western, orig. serialized in the July-October 1931 Triple-X Western as "The Two Gun Kid")

Two-Gun Showdown — The West in Action 4, 1948 (digest-size, western)

Guns Along the Western Trail — The West in Action 2, 1948 (digest-size, western)

Texas Gun Slinger — Star Books 1, 195? (digest-size, western, aka Fighting Horse Valley)

Outlaw Deputy — Star Books 5, 1950 (western, aka Black Sheep)

Dallas — Gold Medal 126, 1950 (as by Will F. Jenkins, western, movie tie-in)

Son of the Flying Y — Gold Medal 161, 1951 (western, as by Will F. Jenkins)

Cattle Rustlers — Ward Lock 1952 (western)

Malay Collins, Master Thief of the East — Black Dog Books 2000 (adventure, coll., 3 stories)

The Seventh Bullet — Black Dog Books 2001 (adventure, coll., 5 stories)

He wasn't Dean

of Westerns, though, or even Romances. He was, for all his work in other areas,

one of US; then, now and forever. Writing for whichever market would pay him wasn't

an indication of hackery, mind you, it was quite a common thing in the days when

almost every conceivable subject had its own pulp magazine.

[i] Robert E. Howard, he of the cowboy hat and mighty-thewed

barbarians, wrote boxing yarns, and even that other Dean of science fiction, Robert

Heinlein, wrote teen confessions. [ii]

He wasn't Dean

of Westerns, though, or even Romances. He was, for all his work in other areas,

one of US; then, now and forever. Writing for whichever market would pay him wasn't

an indication of hackery, mind you, it was quite a common thing in the days when

almost every conceivable subject had its own pulp magazine.

[i] Robert E. Howard, he of the cowboy hat and mighty-thewed

barbarians, wrote boxing yarns, and even that other Dean of science fiction, Robert

Heinlein, wrote teen confessions. [ii]

He wanted

to become a chemist. This ambition, unfortunately, spiraled down the Porcelain

Facility of Fate when his father went broke and took a job at an auto dealership

in Cleveland (yes, they had such things in 1909). Jenkins, at that time making

$3.50 a week as an office boy, had

"...a frantic

frenzied horror of working for somebody else."

So, out of school and with

no hope whatever of going on to college to become a scientist, he began writing.

At least, he began putting words on paper:

He wanted

to become a chemist. This ambition, unfortunately, spiraled down the Porcelain

Facility of Fate when his father went broke and took a job at an auto dealership

in Cleveland (yes, they had such things in 1909). Jenkins, at that time making

$3.50 a week as an office boy, had

"...a frantic

frenzied horror of working for somebody else."

So, out of school and with

no hope whatever of going on to college to become a scientist, he began writing.

At least, he began putting words on paper:

That changed

at least a little when I checked Groff Conklin's

Science Fiction Adventures in Mutation

(Vanguard 1955) out of the library

and read a disturbing little story titled "Skag With the Queer Head" by someone

whose name I didn't learn to pronounce correctly until just before meeting him:

our subject, Murray Leinster.

That changed

at least a little when I checked Groff Conklin's

Science Fiction Adventures in Mutation

(Vanguard 1955) out of the library

and read a disturbing little story titled "Skag With the Queer Head" by someone

whose name I didn't learn to pronounce correctly until just before meeting him:

our subject, Murray Leinster.

Most of

the story is taken up with desperate speculation. How can We trust Them? What

can We do to prove that They can trust Us? Is commerce and communication with

another race worth the risk of annihilation? The debate rages in the human ship,

while the two most important characters—Tommy Dort, a photographer in the

observation staff of the human ship

Llanvabon

,

and an alien crew member Dort calls Buck—get to know each other as well as

circs allow, sending messages back and forth while their respective Captains sweat

it out. One communiqué in response to the

Llanvabon's cautious message of hope for friendship

says it all:

Most of

the story is taken up with desperate speculation. How can We trust Them? What

can We do to prove that They can trust Us? Is commerce and communication with

another race worth the risk of annihilation? The debate rages in the human ship,

while the two most important characters—Tommy Dort, a photographer in the

observation staff of the human ship

Llanvabon

,

and an alien crew member Dort calls Buck—get to know each other as well as

circs allow, sending messages back and forth while their respective Captains sweat

it out. One communiqué in response to the

Llanvabon's cautious message of hope for friendship

says it all: