from Rotarian

Ain't Got Time!

by Ellis Parker Butler

Ellis Parker Butler needs no introduction to Americans -- and little to that wider circle where "Pigs Is Pigs" evolved so many chuckles. He is one of the most prolific humor writers of the day.

The other day I was looking at the Rotary emblem -- the cog wheel -- and I had a great thought, one of the thoughts that only come to immensely brainy men and only when their high-powered brains are free from carbon and sparking on all eight cylinders. The first invention of modern machinery was a clock!

When this thought came to me I was so excited I went out on the back porch and yelled three times, because it is a tremendous thing to think of something no one else has ever thought of, but I am now passing the thought on to you, and anyone who feels sufficiently excited has my permission to go out on the back porch and yell any number of times from three to thirty, either in a low throaty tone like a bull frog or in a shrill piercing note like a cat with a stepped-on tail. The first modern mechanical invention was one to record the passing of time!

And more than that. Every invention since then that is of utilitarian importance to mankind has been an invention intended to save time! First a man invented a machine to divide the day into hours and minutes and seconds -- showing that there was such a thing as a second -- and ever since then men have been inventing machines to save some of the seconds and minutes and hours.

For this discovery I expect to have my statue erected in the middle of the public square, and I have already picked out a handsome six-foot man to pose for it so it will not look as much like a tub as if I posed for it myself.

Of course, like most great discoverers, I may not be absolutely correct in my facts. Great discoverers are not supposed to be. Columbus, you'll remember, thought he had discovered the coast of India when he bumped into America, but his general attitude was correct -- he knew he had discovered something that was worth shouting about, and I feel the same way.

What I have discovered may not be true, but it is interesting. In its general essence it is true.

Away back in the year 4150 B. C., which was in the reign of King Tosorthros of Egypt, 6,075 years ago, copper tools for workmen were first invented and the copper adz may be called a machine to save time if you want to look at it that way, it being much quicker to knock the rough edges off a limestone slab with a copper adz than to bite them off with the naked teeth; but to my notion a copper adz does not come strictly under the head of Machinery, not having many working parts and no cog wheels at all. I class the copper adz under Tools, with the knife and fork, hairpin and pipe cleaner.

I don't deny, either, that along about that same time, in Egypt, somebody invented what might be called a machine. It was used to lift water from the Nile to the higher levels, where it ran through gutters and irrigated the land. In its general construction this was a long pole with a bucket on one end and a bare-skinned native on the other, but -- strictly studied -- it should probably be called an apparatus rather than a machine. Certainly it could not be wound up like a clock. It had no cog wheels. True, it had to be oiled now and then, but the oil was rubbed on the outside of the native and not squirted into his bearings as in proper machines, so I don't call it a machine.

Before the clock was invented there were some rough and rude attempts to measure time, but time wasn't worth much then and the time-measuring apparatus was nothing to get out a twenty-four-page booklet about. There were sundials in ancient times, but the man who had an appointment to meet his wife at the corner of Pyramid Avenue and Sphinx Street at 3:30 P. M. and ran into a cloudy day was up against it. He could look at the sundial until he was blue in the face and he was no better off. There is a painting on the inner walls of the tomb of Thothmothes, with an inscription that was translated by the late Professor Xerxes J. Fliggis, that would make a Silurian wombat weep, and it is known that the Silurian wombat has no tear ducts at all. In fact it has no eyes. To be perfectly frank, there is no such animal.

At any rate this painting in the tomb of Thothmothes indicates that he was a wealthy gentleman in the cloak and suit business and it shows him coming home sometime along in what the intellectuals call the G. M. after quite some party at the Heliopolis Poker Club. He was, I am sorry to say, considerably lit up, and his track from the Club to his home looked like a map of the Mississippi River. That was before prohibition, of course.

Well, it seems that this man Thothmothes had promised his wife to be home by eleven o'clock P. M. and she had sat up waiting for him. For an hour or two she sat up reading the Heliopolis Times, and then she sat up a few more hours reading that interesting novel, The Flapper of the Nile, which was a picture of how the younger set was getting faster and faster every century, and when she had skipped Chapter XXV and finished the book she just sat up and waited, holding the rolling pin in her right hand and slowly opening and shutting her left hand with the motion of a tigress about to scalp something.

Along about 4 G. M., when the night was at the darkest, Thothmothes opened his front gate carefully and took a look at the front of the house. He saw the light of an olive-oil cruse in the living room window and he guessed that his wife was waiting up for him. He wondered vaguely what time it was and what he would tell his wife, and just then he remembered the sundial and he staggered up and took a look at it. It was jet dark and the sundial registered no minutes past nothing. And that is a thing you can't tell a wife who has been waiting up for you; she won't believe it. Any man knows better than to enter the house and say "M'dear, 'ts all ri'--'ts only no minutes past nothing." Thothmothes shook his head sadly and decided to sleep with the dog, out back of the house, that night, but just then the full moon came out from behind a cloud and shone full on the face of the sundial. To his surprise Thothmothes saw that the sundial registered exactly ten minutes past ten. Frankly, he was amazed. He thought he had spent more time than that at the Club, but he braced up and went into the house and said to his wife, "Now, not a word out of you -- it's only ten minutes past ten, and you can go look at the sundial if you don't believe it."

They buried the rolling pin with him.

Later on, probably because of the increasing mortality among clubmen, the sundial was superseded by the clepsydra, a small glass vase by which the water dropping through a small hole in the bottom of the vase allowed the level of the water remaining in the vase to register the minutes engraved on the sides of the vase. This was better because it worked day and night, but when the water supply was shut off because last month's bill was not paid the calendar was shot all to pieces. A timepiece that registered midnight last Tuesday when it was four o'clock in the afternoon today, was not strictly reliable. Anyway, a timepiece that had to be filled with water every little while, like an automobile radiator or a wet battery, was not the best possible.

It was probably a man crossing the Desert of Sahara, who ran out of water and had to drink the contents of his timepiece, who invented the hourglass with sand in it. He had plenty of sand right on the spot.

The hourglass continued to be the popular timepiece for centuries, and it was not until the beginning of the up-and-coming modern era that Henry de Vick, a German, erected the first clock of which we have any record. That was in the fourteenth century, thirteen hundred and something, and he made the clock for Charles the Fifth of France. This was the old style clock with a weight and wheels, the pendulum clock not being invented until about four hundred years later, and the small tin alarm clock with the gong not coming along until roosters were no longer allowed to roost in bedrooms. The tin alarm clock was invented by a man who wanted to get up early one morning to go fishing. It was not called a Ford until much later when wheels were put on it. Watches were invented during the great year of the plague of rheumatism in Europe to relieve the suffering of rheumatic gentlemen who found it painful to carry grandfather clocks to and from business. The first watches were shaped like cantaloupes and were of about the same size but noisier, sounding like hail on the bottom of a tin wash boiler when in action. It was not until much later that the watch was gagged and silenced and it is only recently that the modern thin watch has come into being, the latest improvement being a watch that is so thin that it can be lost between the pages of a pocket memorandum book.

By this it will be seen that while the clock was the first invented machine, and that while it was invented to record time, the progress of the improvements in time-telling machines has been in the direction of making it possible and then increasingly convenient for man to carry his time-teller with him, until at last there was invented the wrist watch which a man can buckle onto himself and take to bed with him, thus having his time machine with him day and night. From the savage who did not care much what century he was living in, we have progressed to the man who wanted to know what year it was and then to the man who wanted to know what day it was, to the men who counted the hours and thus down to the men who found that a minute was worth taking notice of, and so to Nurmi who can get a front-page double-column display ad absolutely free every time he clips a fifth of a second off a record.

What this means is that with each succeeding year the minutes became better worth considering. And immediately men began inventing machines to save minutes. The printing press was invented to let men print twenty books in the time it took them to engross one by hand, and the press has been improved by new inventions until now ten thousand books can be made in the time it used to take to make one. Steamships rush across the seas to save time, and railway trains roar across continents to save time. The telephone carries messages with lightning speed to save minutes for us and the automobile saves us hours. As soon as man had invented a machine to show him what a minute was he began inventing machines to save minutes. He has been inventing machines to save minutes ever since.

I remember an old shoemaker who actually made shoes, although you may not think that is possible. Probably it was back in 1877, when I was eight years old, because I remember I wore copper-toed boots with red tops. He did not make those boots, he bought them ready made and kept them in the original case, something like a coffin box sawed in two, and there they were, all helter-skelter. He would get up from his leather-seated bench and paw around in the box until he found a pair somewhere near your size. I used to stand and watch him by the hour as he made shoes and boots, placing the brown paper patterns marked "Herr Hentz" or "Herr Rogers," cutting around them with quick sure motions of his keen blade, putting the leather to soak, stretching it over the personal lasts that represented the feet of Mr. Hentz or Mr. Rogers. You could study the progress of Mr. Hentz's corns and the growth of Mr. Rogers' bunions from year to year, if you wished, by taking note of the additional layers of leather the shoemaker pegged to the lasts of those gentlemen.

He made a good boot and charged a good price for it, but very few of his customers ever put on a pair of his boots and wore them as they came from the shop. Someone always "broke them in" first -- some friend with a slightly smaller foot. Minutes were not counted as closely then as they are now; a delay of a week or two in getting into one's boots did not matter. Now, when the shoeman says "Will you wear them home?" the answer is usually, "Yes."

My old shoemaker friend worked long and hard. His cobbler's bench was almost as much a part of him as his face was, and not much more leathery. He worked so long and so steadily that his back was rounded just like a banana; and he could no more stand upright than an ironwood boomerang can straighten itself. He often reached his workbench at seven in the morning and he usually worked late into the night, a smoky kerosene lamp hanging down from the ceiling with a silvered glass mirror that he could adjust so as to throw the beams where he wanted them. If you have ever seen one of these old shoemakers, his mouth full of square shoe pegs, jabbing in his awl, sticking a peg in the hole, whacking it with the hammer, jabbing with the awl again, you'll never forget the picture. Or waxing the long linen thread with a seal-red ball of beeswax, twisting onto the end the boar's bristle that was used for a needle and then, with both arms flying wide, sewing double -- one thread from each side -- like a man who will be fined a million dollars if he loses a minute.

He had a sewing machine -- machinery was already beginning to save minutes for him -- and at some place during a job he would get up and go to the machine and swear at it in fervent low-voiced German. "Ach! Gotterdammerung lohengrin hohenlohe spechtnoodle!" he would say as he poked the thread at the eye of the needle, his hand trembling with rage as he knew he was losing a minute.

Now, probably, our shoes are made by men who work under an eight-hour-day rule, and everybody still has shoes to wear. Six hours -- 360 minutes a day, 108,000 minutes a year, 5,400,000 minutes in a 50-year life -- have been given to the shoemaker by machinery that saves time. What is done with the saved time?

For one thing, I believe, those who work do not have to work as hard as they did. Quite a lot of the time is given to pleasures; my cobbling friend would never have had time to go to a movie in the evening; Saturday afternoons never meant a baseball game, either as a player or on the bleachers. But a lot of this machine-saved time goes to make life pleasanter for all. I don't know how many old-style cobblers would be needed to shoe this world today, but I do know it would be a lot more than now work in all the shoe factories. The surplus -- those not needed to make shoes -- are making things like bathtubs and plumbing fixtures, porcelain bathtubs fit for Roman emperors but which every workman has a right to own now and which even the well-to-do did not have in our town in 1878. I took my bath every Saturday night in a tin tub shaped like a saucer, and the hot water came out of the tea kettle.

Much of the time saved to labor by machinery has gone into the manufacture of comforts and luxuries, and in that America leads the world. Not long ago I had a conversation with one of the greatest French Socialists who had been visiting America -- a remarkably fine man. I asked him what he thought of the future of Socialism and Communism in America, and he threw up his hands.

"They will never come here," he said in effect. "They are not needed here. The other day I was in Chicago and I did some investigating. I went to the homes of the workers -- bathtubs everywhere, hot and cold water! Imagine! Bathtubs such as but few of even the wealthy have in my country! No chance for Socialism here; it is not needed."

The minutes the timesaving machines have saved for the laborers have been put to work to better the life conditions of laborers, you see. That's good; nobody kicks about that.

Not long ago I was in my hometown, out in Iowa, and on Saturday evening in order to hasten to an engagement I had to get off the sidewalk of the main street and walk in the gutter, the crowd was so dense. It was up onto the sidewalk and then dodge into the gutter, and up onto the sidewalk again. And every time I stepped into the gutter I came near to being bumped to Kingdom Come by an automobile -- the street was full of them, mostly farmers' cars. I spoke to a local merchant about it and said the Saturday night trade must have improved immensely in volume since I was home before.

"Don't you believe it!" he said "We do hardly any business to amount to anything on Saturday nights -- not half what we used to do. These people come in on Saturday nights to go to the movies; farmers from five, ten and twenty miles out. No, Saturday has played out as a shopping and marketing day. A farmer, if his wife needs a spool of No. 60 cotton thread and happens to mention it at noon, jumps into his car, runs into town and buys it, and is back home before his lunch hour is over."

Machinery has done that -- the automobile, the automatic milker, the farm tractor. The farmer and his wife -- she has the washing machine and all the modern household machinery -- read more, get about more among their friends, have more amusements. I believe that within a few years it will be found that the machine called the automobile will have cut down insanity among farm women -- it was pretty bad, too -- to one-half or less what was formerly thought normal. The automobile not only gets the farmer's wife to her friends and to town, but it saves her the minutes to spend.

But in California a man told me that he and his wife, with a ranch some 40 miles from Los Angeles, used to start at daybreak over a sandy road with a team of horses, camp wherever they happened to be when night came, get into Los Angeles some time the next day, do their trading and start back, camp another night on the road, and get home late the next day -- three days in all. Now they leave home, make the trip at 30 miles an hour -- say an hour and a half -- do their trading, and get home inside of four hours. The time saved is something like 32 hours out of what used to be a 36-hour trip. The thanks are primarily due to two machines, the automobile that carries them and the concrete mixer that made the good roads possible.

All this is, of course, trite stuff and you have all doubtless thought the same things many times. Machinery has made a new distribution of human labor activities necessary, and that distribution has taken place more or less gradually and will continue as new machines are invented.

I remember hearing a man in St. Louis, not long after the war, make a crop prediction for Missouri for the year. Some speaker had spoken of the seemingly alarming desertion of the farms. A great many of the young men who had left the farms to go to war were not coming back to the farms but were going to work in factories, and still other men wore deserting the farms to go to work in mills and shops. In spite of this the speaker predicted that Missouri would have the biggest crop she ever had, and he was right. He based his prediction on the theory that very few of the men leaving the farms were actually leaving the farms. They were going to a new part of the farm, but one just as necessary in these days of machinery. Instead of staying in one corner of the farm and raising horses to pull plows they were going to another part of the farm -- the tractor factory, for example -- and making a machine that would do more and better plowing than the horse ever did.

There is a lot of sense in this idea. It seems to be an actual fact that the more men leave the farms the more the farms produce that human beings can eat. With the tractor taking the place of the horse the hayfield is not needed for hay and can grow potatoes or wheat. By and by, possibly, all the men will leave the farms and the farms will produce so much food that we'll all have to eat six meals a day. But that won't be for quite a while.

What interests me, however, is what you and I have gained by the invention of machines that save minutes for us -- the saved minutes of our own personal days, saved by telephones and typewriters and mimeographing machines and all the various machines that assist the man with an office and the man with a shop. At a first glance it may seem that we are not getting a square deal from the inventors of minute-saving machines; that the laborer and the farmer have all the best of it. But I'm not so sure! Even buying a pair of boots used to be a genuine time-waster in your grandfather's day; when all boots had to be made to order there was a lot of fitting and trying on and bargaining about price. A good many minutes a year went into it, and a good many minutes a year went into being measured for shirts and suits and other garments. Time went into walking to and from business where the streetcar and the automobile now save hours every year. Letters were written in longhand that are now dictated to a stenographer and whacked out on a machine.

We have our share in all the comforts and luxuries made possible by the release of labor from the making of necessities. We think no more of having three bathtubs in a house than we used to think of having a tin basin on the back porch. We are a mighty lucky generation and living in a mighty fortunate age.

Looking about in a casual sort of way I can see you doing a lot of things your fathers and grandfathers could not do because timesaving machines had not reached their present general use. You may take your membership in Rotary as one of these. If anyone had asked your grandfather merchant to take time from a weekday noon to go to a hotel and eat a full luncheon and then listen to talks he would have wondered if he was suspected of being crazy. Only one out of a thousand merchants had time to do all that was necessary in shop or factory or store in a long hard day. Even the grocer who now reaches out a hand and picks from his shelf a neat package had to spend hours wrapping sugar and oatmeal and salt. A machine now wraps them for him in a factory. The doctor had to spend hours driving his "safe" horse from patient to patient -- now he looks at his watch, allows eight minutes by automobile to reach his patient, and attends a Rotary meeting in comfortable leisure. The cog wheel is a fit emblem for Rotary; the invention of machines made Rotary possible.

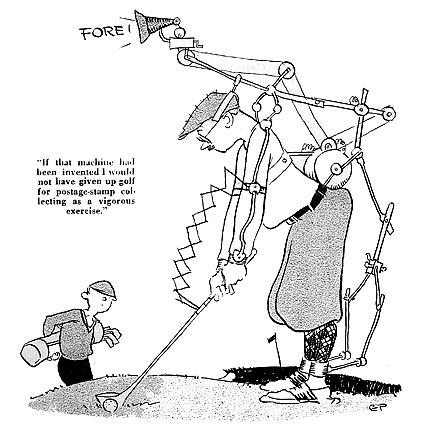

There could be no golf, now the most numerously practiced game in America, had the telephone not saved hours each week for us. There would be no golf courses of the superb American quality -- we could not afford them had someone not invented the mower drawn by horse power and the motor driven by gasoline. The only pity is that someone did not invent a machine to attach to the man who does his eighteen holes in a neat little 124 so that he could go around in about 80. If that machine had been invented I would not have given up golf for postage stamp collecting as a vigorous exercise.

But none of this worries me. What does worry me is just where the men are being cheated who, when asked to take part in anything worthwhile, always answer "Ain't got time!" or words to that effect. I hear this often myself and all of you hear it now and then whether the matter is a game of golf, a little help in the excellent work being done for boys, or any one of the great number of civic, social, and charitable activities.

I'm not going to blame the man who answers "Ain't got time!" as regularly as the clock ticks, because he ought to know whether he has time or not, but I do think that he must be cheated somehow. If his grandfather was in the same business he is in his grandfather probably had to give every moment to his business, and I can understand that -- his grandfather had none of the modern timesaving machinery. His grandfather had no telephones, no typewriters, no card systems, and he possibly had to go out in the winter and break the ice in the creek before he could take his bath. If his father was in the same business I can understand why he, too, had to give every minute to his business or profession. But if the modern business or professional man has no minutes to give to play and sociability and good deeds he is being robbed and he ought to do something about it. Someone else is getting away with the minutes saved for him by timesaving machinery.

As a matter of fact "Ain't got time!" is the poorest excuse extant. It is usually the last refuge of the man who wants to side step something he doesn't want to do and knows he ought to do. I have used it hundreds of times myself on days when I felt that a nice little snooze on the couch in my library would just about suit me. The "busiest" man in any town is usually the second-hand goods dealer; he never has time for much of anything and you'll usually find him asleep in an old rocking chair with a cobweb reaching from one of his ears to the inert pendulum of a deceased clock nearby and the dust so thick everywhere that a junebug would drown in it. "Well, I would, but I ain't got time!" is his motto. The minute he wakes up and begins to have a few minutes a week to spare he is out of the second-hand game and becomes a dealer in antiques and people rush to his shop and pay sixty-eight dollars for a joint of second-hand stovepipe of the late McKinley period.

Under the Constitution and By-Laws of the United States every man starts breathing with twenty-four hours a day that are all his own. These are ticked off into minutes right from the start. At first they are divided into periods devoted to sleep, colic and sucking his thumb, but presently he gets into a business or profession. The minute he does that the innumerable timesaving machines begin saving for him minutes his forebears in the same lines could not save. It means, in effect, that any man who knows how to properly organize his day ought to be able to do as much in seven hours a day as his grandfather could possibly do in twelve hours. I believe in every man being more efficient than his grandfather, so I'll say the man ought, perhaps, to work eight hours a day and thus do as much as his grandfather did in fourteen hours. But the rest of the saved time ought to be spent in sport, amusement, good companionship, and general good citizenship.

If that's not so all the machinery in the world don't amount to a cent to you. It might as well be scrapped. We might as well go back to the old days when wife boiled the soft soap in the iron kettle in the back yard and you whittled the point of a quill pen with a desk knife, sprinkled sand on your letters and sealed them with wafers.

The man who, today, has to say "Ain't got time!" is right in the class with the man who says "Ain't got money!" He's poor and we ought to feel sorry for him. That man gets the best out of life who always has a few spare dollars in his pocket and a few spare minutes in his hour. Of the two the latter has all the best of it. Nearly all of us can spend a few spare dollars, but, oh, boy! How the worthwhile fellows do welcome the man who has a few spare minutes to spend!