from Country Gentleman

A Bump on the Head

by Ellis Parker Butler

When Frowzy Frank came to his senses, of which there are five -- seeing, feeling, smelling, tasting and hearing -- he tasted and smelled nothing. What he heard was a loud throbbing inside his head and what he felt was one big pain. What he saw was jagged streaks of red and purple lightning. He glared at this amazingly vivid and active electric display a moment and then tumbled forward again, this time with his face in the cinders, once more unconscious.

His history up to this point is a short and simple annal. At eighteen, his name being Frank J. Carnoy, he ran away from his home in Kansas and since that day he had been a tramp. In all, he had been inside three hundred jails, had ridden in some three-thousand box cars and had taken about thirty-six baths.

Eight times he had been blackballed from membership in the I. W. W. as being too worthless to be considered a human being, and he had not a friend in the world. He was so unutterably lazy that even the most worthless tramp would not associate with him.

He went it alone and he was probably the most disreputable, frowzy, indolent, no-account specimen in existence. He had now reached the age of forty-five years and had never done a lick of work, but until the night before this day he had not committed a crime. He had been too lazy.

The night before this day Frowzy Frank had made the great mistake of his life and had done a job of sneak-thief burglary. Walking along one of the residence streets of the city of Talavera, he had chosen a house from which to beg a handout, but when he walked to the back door he found it locked. Coming toward the front again he saw an open window, low enough to enter without much trouble, but he had no thought of crime until he reached a clump of bushes at a forward corner of the house. Then he heard the front door being closed, and heard a woman's voice.

"Be sure and lock the door, Martin," the voice said. "Cook is out, and I left all that money in my purse on my dresser."

When the couple had disappeared down the street in the dusk, Frowzy Frank went back to the window and climbed in. First, he rummaged for the money and found eighty-six dollars in the purse on the dresser -- more money than he had ever had at one time in his entire life, almost more than he had had in total up till then.

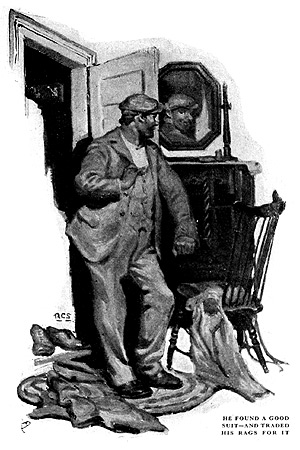

In the kitchen refrigerator he found food and a bottle, and it was after he had eaten heartily and emptied the bottle that he prospected in the upper rooms for clothes. He found a good suit in a closet -- a business suit of honest gray tweed -- and traded his rags for it.

He found a pair of brown shoes, rather well worn, and when he had put on a pair of blue socks he put on the shoes. In the hall below he found a gray tweed cap and he exchanged his own greasy cap for this. He left the house by the same open window, slunk along by the hedges and buildings until he reached the railway tracks, and there he hopped a passing freight train, pulling himself up into a box car as the train slowed down.

The stolen clothes and hat and shoes did not greatly change his appearance. His face was still hairy, his eyes heavy and his gait shambling. He was still completely and entirely tramp. He threw himself on the floor at one end of the box car and went to sleep, snoring amazingly.

Early the next morning the train found itself many miles from Talavera, approaching the much larger city of Steelton, and Frowzy Frank was awakened by the sudden jolting of the train as it stopped at a track intersection, throwing one car back against another. He awakened to see four other tramps standing in a group at the far end of the car, whispering together and eying him. The ugliest of the four, a redheaded giant, held a wooden club in his hand and it was evident they meant to attack him. He knew why. They wanted the clothes he wore.

As the train jolted forward across the tracks Frowzy Frank was alert. The door of the car stood well open and the train had not gained much headway; scrambling to his feet he made a dash for the open doorway but the red-headed giant leaped for him and struck. The blow came too late to be of service to the tramps, but it struck Frowzy Frank on the back of the head and he pitched forward out of the car, falling on his face on the cinder-ballasted right of way, catapulting thence down the side of the embankment some fifteen feet.

There he lay unconscious. Only for the brief moment already mentioned did he regain consciousness; then he swept back into nothingness again. It was still early in the morning and crisply cool. Some fifteen feet from where Frowzy Frank lay, a street crossed the tracks of a trolley line and presently laborers, early on their way to work, began to pass in twos and threes.

None of these happened to notice Frowzy Frank where he lay for they glanced up and down the trolley track before crossing, but a quarter of an hour later the laborers became more numerous. One group of young fellows were roughing one another playfully, chasing one another, and at the crossing one made a dash for another, running him off the roadway, and they saw Frowzy Frank.

"Hey, fellers, come here!" they called. "Here's a dead man!"

The gang crowded around Frowzy Frank and in a minute a crowd had formed and presently a policeman appeared, pushing through the crowd. He knelt by Frank and turned him over, taking charge instantly. He asked questions and found that no one had seen the accident, examined the tramp's wounds, his abraded hands and garments, went through his clothes and found a bunch of keys, a fountain pen and eighty-six dollars. He went to the nearest telephone and called an ambulance.

While he was awaiting the ambulance he examined the near-by ground, for he was a young officer and keen. He found nothing to indicate a struggle but, as he widened his circle he reached the planking that rilled the roadway adjacent to and between the trolley tracks. Across these planks and ending on what would have been the sidewalk had there been one were four broad smears of rubber such as are made by the wheels of an automobile when the brakes are set suddenly while the car is going at full speed and the tires scrape the road. These tire marks came from the far side of the trolley track toward the side on which Frowzy Frank lay, and they curved toward him.

The young policeman instantly visualized an automobile accident. He saw a well-dressed citizen walking in the roadway, a trolley car approaching, an automobile driver speeding to cross ahead of the trolley car and the driver suddenly seeing the citizen, throwing on his emergency brakes and swerving, but hitting the man hard.

The car must have been going at unlawful speed, he judged, for it had thrown its victim fifteen feet, had broken his nose and given him a bad blow on the back of the head and had cut him up considerably. Possibly it had broken bones as well.

"Them drivers!" he ejaculated. "A lot of them ought to be in the pen. But this guy may have been drunk at that, out in the middle of the road that way."

When the ambulance arrived from the Emergency Hospital -- "largely supported by voluntary contributions" -- the young intern examined Frowzy Frank's wounds and got him onto the stretcher and the police officer sat beside him in the ambulance and told him his theory of the accident as they hurried to the hospital.

There the surgeon in charge examined Frowzy again and the proper entries were made, detailing that "M. J. N." was the victim of an automobile accident, and in due time Frowzy Frank was bathed, his wounds dressed, his broken leg set and put in splints, and he was put to bed in a ward. His excellent tweed suit, cap and brown shoes, his keys and his fountain pen, and his eighty-six dollars were sealed in a heavy paper bag and put in a locker.

During the night Frowzy opened his eyes and asked for a drink, but when he awakened the next morning he was unable to speak clearly and seemed dazed. That day he was shaved, but he lay in a state of semiconsciousness, only groaning now and then when he tried to move.

Day after day he was bathed and twice a week he was shaved. As his hair had been rudely shorn to lay bare the wound at the back of his head his hair was cut by the hospital barber. He was well treated in every way, as was becoming for a citizen who had had eighty-six dollars in his pocket at the time of his accident.

Gradually he improved and in a few days he was able to use his tongue a little. In three weeks his leg bones had knit and his only trouble seemed his general nervous condition. His broken nose was healed and the wound at the back of his head had revealed no fracture. The head nurse, the chief of staff and the superintendent decided that the case was going to be a long one. The patient had no use of his legs whatever.

Evidently the case was no longer one of the sort for which the Emergency Hospital was meant and they made out the proper requisition papers to have him taken to the Steel County General Hospital, where he could remain as long as necessary. Copies were made of all the records in the case and Frowzy was loaded into another ambulance and taken to the larger hospital.

When he arrived at the General Hospital, dressed only in a nightgown, one of the Emergency Hospital bathrobes and a pair of paper slippers, Frowzy was entirely unlike the man who had been carried into the Emergency Hospital. He was immaculately clean, well barbered and pale. Every trace of alcohol had been washed out of him.

One hospital is less like another than one city is like another. The inhabitants are different; there is no interlocking of interests; to go from one to another is like going to a far land. None in the General Hospital had ever seen Frowzy before; they took him as he was reported to be by the Emergency Hospital staff. They found him clean and his records said he was an automobile-accident victim, and his clothes and money suggested he had been a citizen of no mean standing.

Over his head, when they put him in bed, was placed the identification card. On it he was given a number -- 12,768 M, the M meaning he was now a medical case. He was further specified to be "White," and "Male" and "M. J. N. -- name unknown," but after the word "Religion" a query mark was written, because, although he was duly questioned, he declared he did not know what his religious belief was.

The line for his address was also left blank. When they asked his name and his address and if he had a wife or any close friends, he said he could not remember. They brought his clothes and his shoes and the cap with the initials in it and even his eighty-six dollars, but he said he could not remember anything about them. He examined them curiously and with interest, but he said he did not know whether they were his or not.

Aside from this total loss of memory, his principal ill seemed to be the loss of all ability to use his legs. When they tried standing him on his feet he fell down. He could use his hands and arms normally, but he could not so much as move one toe. After many tests the physicians said he was not malingering, and a long and scientific treatment by massage began, and when at last he was able to move a toe Frowzy was the happiest of any of them. From that moment he improved rapidly and in a week he was able to stand alone and take a few steps; in two weeks he was quite well again except for his memory -- he could remember nothing.

It was now impossible to keep him in the hospital any longer, but it would not do to put into the streets a man without a memory. There was some talk of letting him take on a job as orderly in the hospital, but the manager would not hear of this, pointing out that the patient was evidently a man of some moment and that the orderlies were mostly poor trash.

In this emergency the manager properly appealed to the police. The records showed that on a certain September day this patient, most probably a citizen of Steelton, had been struck by an automobile while walking on the street, and his money, suit and shoes showed that he had not been poverty stricken. The inference was that he must be somebody, and there was a possibility that the police might have a record of a missing man.

When the appeal reached the chief of police, which it did very promptly, he sent a bright young detective connected with the Missing Persons' Bureau to look into the matter.

The young detective's name was Burke and he spent a full morning looking over the records and photographs of missing persons, comparing them with the description telephoned by the hospital's manager. He reached the hospital about one o'clock and Frowzy was taken to the manager's office to confront him. He seemed eager to go, at least he went willingly. At the conference were also the manager, Doctor Gillis, who was a young intern, and the head nurse.

"This the man?" the detective asked, looking Frowzy up and down as he entered.

"This is the man," the manager replied.

Burke studied Frowzy carefully. The detective's eyes were keen -- hard blue photographic eyes that took in every detail and registered it permanently.

"Well, Nolan," he said suddenly, his eyes jumping to Frowzy's eyes and pinning them, so to speak, "I suppose you know your wife is dead?"

Frowzy blinked as if a light glared into his eyes.

"Wife?" he said vaguely. "I don't know nothin' about no wife. You see, mister, I don't remember nothin'. I got a bump on the head and me thinker quit work on me. Ask him. That's what he says. I don't know nothin' about it."

"You know your name, don't you? You know your name is Michael J. Nolan, don't you?" Burke demanded. "You know your name is Mike, don't you?"

"Mike?" said Frowzy, turning it in his mind. "Mike, hey? Well, maybe it is, mister. I don't know is it or ain't it."

"If your name's not Mike what are these letters in your cap for?" asked Burke, showing him the tweed cap. "This is your cap, ain't it, Nolan?"

"It looks like it is," Frowzy said. "These folks say I had it on me when I got bumped anyhow. I don't know nothin' about it; I can't remember I ever seen it until they showed it to me. You see, boss, I can't remember anything --"

"Does Maggie mean anything to you?"

Frowzy repeated the name. He closed his eyes and repeated it again.

"No, it don't, boss. It don't mean a thing. Who is she?"

"She was your wife," said Burke.

"What wife?" Frowzy asked. The one you was talking about -- the one that you say is dead?"

"Why?" Burke asked quickly, boring into Frowzy with his eyes. "Did you have more than one wife?"

"I don't know. I don't know did I have any; maybe I did and maybe I didn't. You see, boss, I got me a bump on the head --"

"Forget that bump on the head," said Burke. "Get your mind onto what I'm asking you. Now, listen -- does Patrick mean anything to you?"

"Sure! Sure!" exclaimed Frowzy eagerly. "Pat's th' orderly over to our wing of the hospital."

"And don't Pat mean anything else to you?"

"Say, I wisht I could say it did, boss," Frowzy said. "I don't seem to could, though. You see, boss, these folks says there was an accident and I got a bump --"

"Never mind the bump," Burke said. "Tell me this -- can you remember anything about Mary, huh? Or Aileen?"

"You can search me!" Frowzy declared. "Maybe I ought to remember them, but I'm poor off that way. You see, boss, it seems like this automobile come along and tossed me onto my head --"

"Take a look at this cap," Burke ordered. "Can you read those letters punched in the sweatband?"

Frowzy studied the letters, which were composed of small perforated holes. He frowned as he studied them, and then glanced up at Burke questioningly.

"Sure, I can read them," he said. "M. J. N."

"Well, don't they stand for some name? Can't you remember what name they stand for?"

"You see, it's like this, boss," Frowzy answered apologetically; "me head don't work good -- not so good. I got a bump on it, see? What I mean, this here automobile come along --"

"I know all about that, Nolan," said Burke. "You don't need to tell me. Tell me this instead -- do you remember a place called 8462 Connorton Street? Or anybody named Enderby?"

"Say, for you, boss, I'd remember anything in the world if I could," said Frowzy earnestly. "Honest I would, and that goes! But I got me a bump on the head --"

"Now, stop that! Stop that!" Burke cried angrily, half rising from his chair in menace, but the young intern, Doctor Gillis, interposed.

"You'll have to go a little easy with him, Mr. Burke," he said, "and make some allowance. It's annoying to have him bring in that bump on the head constantly, I know, but you must remember that in memory this man is only a month old. The accident is a tremendously important thing in his short memory-life. Leaving out the days he was unconscious his memory is only a few weeks old, and he hasn't much to remember -- only what has happened in the hospital and the one big event of his life, the accident."

"How old would you say he was, this man?" Burke asked.

"Physically he is forty-four to forty-six," said the intern. "We can never judge exactly, but that is what I would say."

"Go on in that room there, Nolan, and wait a few minutes," Burke said, and Frowzy, after looking toward the intern for permission, went into the small back office, and Burke closed the door. He came back to the little group and turned to one of the papers in his docket.

"Now, this loss-of-memory stuff I don't take any stock in," he said immediately, "and I don't know whether you do or not --"

"We do absolutely," said the intern. "We consider it a case of true amnesia, but whether temporary or permanent only time can tell. We've given him every test known to science and we are entirely convinced."

"Well, I ain't," said Burke flatly. "I've been up against a lot of guys in my day, and I've run across some of these amnesia fellows that were mighty slick. They got away with it good; good enough to fool anybody. And down there at headquarters we don't take any stock in this amnesia business at all. We don't believe there is any such animal, as the fellow said. If this guy has it he's the first I ever saw, and I don't believe it. I guess he can remember if he wants to, just as well as I can. My hunch is that he's trying to fool you so he can beat it out of here when nobody is looking and disappear again, like he did before."

"He had plenty of chances to disappear," the intern said. "He has had his clothes and his money and he might have slipped out any day, but he did not. We told him to wait around and he waited."

"Well, maybe! Maybe!" said Burke, unconvinced but not caring to argue. "I don't know about that, but I do know he got up and vanished and left his family once, and he was fetched back and got up and left them again, and a man that'll do that twice will do it three times."

"You know who he is, then?" the manager asked.

Burke referred to his papers.

"I've got him here," he said, "in black and white, and I took a good look at his photograph at headquarters before I came up here. There's no doubt about it. This man is a dead ringer for the photograph. You got to remember he's five years older now, and that he's been sick and got thin, but he's the same man, right down to the broken nose on his face. His name is Michael J. Nolan, known when he was a tighter as Battling Nolan. He would be forty-five years old," Burke added, referring to his papers. "Bring him in now."

The intern opened the door and told Frowzy to enter.

"What do you say?" Burke asked them. "Is that a fighter's face or ain't it?"

"It certainly does look like a fighter's face, especially the side view," admitted the head nurse.

"Sure it does," said Burke, "and that's who he is. He's Battling Nolan, otherwise Michael J. Nolan, forty-five years old. He left home five years ago, May sixteenth, being then aged forty, to go to work in Samuel F. Enderby's saloon, where he was employed as bartender. He was dressed -- but of course he has on different clothes now. Let me see -- he had disappeared once eight months before then, but the police found him and fetched him back."

"You mean that's me?" asked Frowzy.

"Of course I mean it's, you, and you know it," said Burke.

"I can't remember, you see, boss," Frowsy said. "I got a bump on me head --"

"He was then living at 8462 Connorton Street," Burke went on, "with his wife Maggie and the two kids, Patrick and Mary. Pat was four and Mary was two, but this other one -- Aileen -- wasn't born yet. She was born two months after he skipped out. And that's about all, except that his wife died three months ago -- pneumonia. So there's the facts."

Burke folded his papers and arose.

"Now, I'm clear in my mind about all of this," he said. "The memos the cops took at the time state that this man's wife had quite a tongue, or words that mean that. She was a hottish-tempered lady and she lit into Nolan plenty and often, and he ran away once and said more than once to the neighbors that he would run away again if he couldn't have peace at home -- not that I blame him for that," he added, looking at Frowzy.

"Did he leave the poor thing destitute?" the head nurse asked. "With two children and another coming?"

"I'd not say so," said Burke. "They were living in a story-and-half frame dwelling at said address, which he had put in her name, and he had eleven hundred in the savings bank, which he signed over and left when he went. For three years he sent her money off and on, from different places, and then he quit.

"And here's how I figure it out -- he's been beating it here and there and maybe was nearby and got word of her death and thought he would drift around and see if the house was sold or not. It might be a tidy little sum he could get for it, you see? So he came along and maybe he found the house was sold and the money spent -- which was what had happened -- or maybe he hadn't had time to find out yet, but this automobile hit him. And so here he is. Isn't that what happened, Nolan?"

Frowzy started, for Burke had turned to him suddenly. He put his hand to his forehead, and he frowned, but he shook his head.

"It sounds like it might be somethin'," he said, "but the trouble is, boss, I can't remember nothin'. You ask them, boss. They'll tell you this automobile come along and knocked me for a row of sticks, and I got this bump on me head --"

Burke turned from him in disgust.

"Now, here's what we're up against in this case," he said. "They've had the three kids at the County Farm since this wife died three months ago, and it ain't up to the county to support them if they've got a father that ought to be doing it."

"The thing is, can he? If he can he's got to be made to. You can wipe out the prizefight stuff because Nolan was a dead one before he even ran away. And the barkeep business has gone flooey, like you know. Listen here, Nolan! What was you working at all this time?"

"I got a bump on me head --" Frowzy began.

"There you are!" exclaimed Burke. "If he's got this amnesia, or if he ain't got it -- there you are! He's going to stick to it that he don't know anything. And what chance has a man got to earn a living for himself and three kids when he don't know anything? It's a case, ain't it! Well --"

He prepared to go.

"I'll go back to headquarters," he said, "and have a talk with the chief, and I'll let you know what comes of it. That's all I can say, but we'll just consider that Nolan is under arrest from now on."

When Burke was gone the head nurse appealed to Frowzy, as friend to friend, and had quite a little talk with him. She had no doubt whatever that the hospital's decision that Frowzy had lost all memory of his past was the correct one, and she dealt with the matter on that basis, trying to appeal to Frowzy's better nature.

"There are these three little children, don't you see?" she said. "They are your children -- your little Pat and Mary and Aileen -- and if you don't be a father to them, Mr. Nolan, they'll grow up as paupers. Your own children!"

"My own children," Frowzy repeated. He seemed to try to grasp the idea that he had three children, but it seemed to be difficult to get the idea. "The trouble is I can't remember I had them, don't you see, miss?" he said. "That was before I got me bump on me head, huh? Well, I don't know nothin' about it, see? If this feller says I got 'em, I guess I got "em. What have I got to do about it?"

"Why, you ought to do what every father does," the head nurse explained eagerly. "You ought to take them and have a home for them and -- and love them as a father should. You must have loved them once."

"Say, now you got me beat!" said Frowzy. "Did I or didn't I? I don't know. What you say their names was?"

"Patrick, Mary and Aileen -- one dear little boy and two dear little girls. Let me see -- Patrick must be nine years old now, and Mary seven and Aileen all of five. About so big, probably."

"Say, what do you know about that!" Frowzy exclaimed, measuring Pat's height with his own hand. "Me with a kid that big and I don't know it! Say, I wisht I'd 've met their mother."

"But you did," the head nurse assured him. "She was your wife, you know."

Frowzy sighed.

"I wisht I'd knowed her," he said. "And us livin' in a story-and-half house! Can you beat it? Me and the wife and the kids, livin' in a story-and-half house and I didn't know anything about it! I bet she was a good looker."

"Now, that's right," said the head nurse. "Try to remember what she looked like."

"She looked like you, kid," said Frowzy. "If she was a good looker she did."

The head nurse blushed. She did not often blush, and this blush was not entirely because it was a little disconcerting to feel that this man might -- with his blank mind -- so visualize her as his lost wife that he might always think of her as the mother of his three children. She was not, this afternoon, quite her usual calm self, for she was a little tremulous. Several times in the office young Burke had caught her eye and she had thrilled each time and their eyes had spoken. She was young for a head nurse, and it may be as well to say here that Detective Burke managed to see her often in the following days.

"Now, here's the line-up," Burke said when he came to the hospital the next morning. "I had a talk with the chief, and I went out to the farm to give the kids the once over, and I went to see old Enderby, who was this Nolan's boss back there before prohibition. The chief says we've got to hold Nolan and put him to work and make him support those kids."

"Are they nice children?" the head nurse asked.

"I don't know that I would pick them if I was doing the picking," Burke said. "This Pat fellow looks a good deal of a devil to me, and they say out there he's a terror. He's a redhead, with so many freckles you can't hardly see him, and the whole shooting match's shins are raw from where he kicks them when they try to wash his face or give his hair a comb. Sort of a young riot, I guess."

"And the girls?"

"Well, the Mary kid is black -- black and sulky," said Burke. "She ain't got a use for anything or anybody in the world. That kind of kid. The other one -- the five-year-old -- is a weeper. Honest, I feel sorry for anybody that has to try to handle that bunch. But that is the chief's orders. So I went to see old Enderby, and I got that fixed up. I got Nolan a job."

"I think you are just wonderful!"

"Oh, not so good at that!" said Burke, but he grinned that he appreciated the compliment. "It wasn't so hard. Old Enderby has a big place out on the North Road -- they say he made a pile at bootlegging the first year of prohibition. Anyway, he's retired now, and has a big place with gardens all over it, and he remembered Nolan like a book. He'll take him on and let him be a gardener."

Enderby had agreed to let the new undergardener have two rooms over the garage and the chauffeur's wife had said she was willing to keep an eye on the children. With all this arranged for, there would not be much money coming to Frowzy. A raw undergardener does not draw much pay, and when it is reduced by deductions for rent, meals and the small payment to the chauffeur's wife, there is not much left, but Frowzy was not interested in finance anyway. His interest was all in the three children; the idea that he had three children seemed to overwhelm him -- it was a tremendously amazing thing.

"Say," he asked the head nurse, "what if I don't like them kids? What if they don't like me?"

"You must not worry about that," she told him. "If they don't like you at first you can make them like you."

Frowzy said nothing. He shook his head and was lost in thought.

"If you're thinking that you ran away once and ran away twice and can run away from them again if you don't like them, stop thinking it," said the head nurse. "Really, Mr. Nolan, you were not much good before; now you've got a chance to start all over again."

"Yeh! With a family I don't know nothin' about," said Frowzy. "What I'm scared of is that family. I ought to have a wife come with it; that's what ought to come along with it, a wife. Say, listen, how about --"

The head nurse fled. An hour later a police patrol wagon came for Frowzy and Burke came with it. He suggested that the head nurse had better accompany Frowzy, so she put on her cloak and hat and sat up front with Burke, while Frowzy and a policeman sat at the rear of the patrol wagon.

"This is a good piece of work," Burke told her. "I've got a hunch it is going to work all right, and I wasn't so sure. You still think this fellow's memory went flooey when he got that bump on the head, don't you? Well, I don't believe it a bit. He's pretending. He's leaving it open so he can pretend his memory has come back again if he gets sick of these kids after while, like he got sick of his wife. If he gets sick of them he'll remember he's someone else, see? And say he don't have to stick around.

"But I ain't going to let him pull anything like that on us. I'm going to keep right on this case awhile and look him up good and pin him onto himself for sure. I'm going to start in and trace him, right from the day he skipped out five years ago till the night he got this bump on the head, see?"

"I think you're just wonderful!" said the head nurse again.

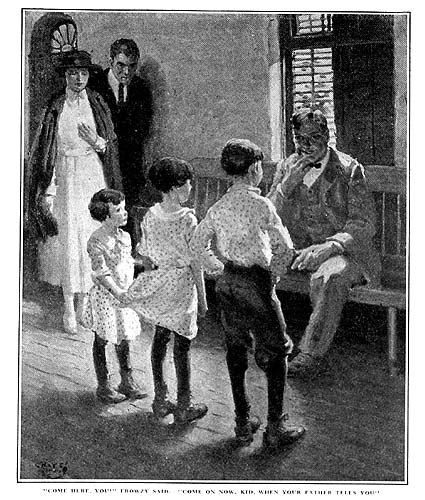

In the reception room at the County Farm they had to sit awhile before the children were brought in. Frowzy seemed nervous. When the door opened and a matron appeared, pushing before her a teary small girl, Frowzy leaned forward sharply and stared. The matron took the child by the arm and led her to Frowzy.

"This is the little girl: this is Aileen," she said. "Aileen, this is your papa."

Behind the matron came Mary, black and scowling, and Patrick, and Frowzy gave the girls a mere glance apiece and looked at Pat. The boy stood looking at Frowzy, not quite grinning, but not quite serious. Their eyes met and clung and presently Pat grinned.

"Come here, you!" Frowzy said. "Come on now, kid, when your father tells you."

"Gee! You got a bum nose!" Pat said, but Frowzy drew him between his legs and held him with his knees. The boy stood grinning into his face as Frowzy felt his arms and his shoulders.

"You got some meat on you, kid," he said presently; "but, gosh! you got some freckles, ain't you? You're some kid, kid! And you ain't got no mother -- and you ain't got no father --"

"Aw, cheese! What's eatin' you? I has, too, got a father; you's him," said Pat.

"Some kid! Some kid!" said Frowzy, looking at the head nurse and putting one arm around the boy. "Say! And you knowed I was your father the minute you seen me, didn't you?"

"Sure I did," said Pat. "Ain't me mother always sayin' you got a bum nose on you where Terry the Terror walloped you when you knocked him out in the second round? Sure I knowed you!"

"And -- and -- and I know you, too!" said Aileen eagerly.

"Why, sure you do! Sure you do!" exclaimed Frowzy, holding a hand toward her and gathering her to his knee. "And you're the one that wasn't born yet, huh? And you?" he asked, looking at Mary the sullen.

"Yes!" she said taciturnly.

It was evident she had been dressed and coached for this meeting, for now she came close to him and held up her lips, scowling.

"She wants to kiss you," said the matron. "She wants to kiss her father."

"Me?" exclaimed Frowzy. He looked at the girl and suddenly he dropped his face against Pat's shoulder. The matron gave the sullen Mary a little push so that she, too, stood against Frowzy's knee. When he raised his head the child's lips were still raised and he kissed her.

"What do you know about that! What do you know about that!" he exclaimed. It was the first kiss a child had given him in his whole life.

"I guess you remember them now, Nolan, huh?" Burke asked, but Frowzy did not answer him; he was looking into Pat's eyes, patting the boy on the back.

"And me the father of them -- me the father of them!" he was saying. There was awe in his voice.

For a few weeks after that the head nurse stopped at old Enderby's now and then on her off-duty time to see how the Nolans were doing. She found the chauffeur's wife a friendly woman, ready to converse. The new undergardener was not much of a worker, it appeared, but the gardener thought he could shape him up by spring so that he would be a good worker -- good enough anyway.

And one thing was sure -- he was crazy about the children. There was trouble sometimes getting him to let them be put to bed and sent to school. Like chums, they were, or -- said the chauffeur's wife -- as if Pat was the father of all of them and Nolan one of the kids. It seemed that Pat talked about his mother a lot, and about the old days before Nolan had run away, and Nolan seemed to be getting over the bump on the head and to be remembering things again.

The chauffeur's wife herself had heard him correcting Mary once, telling her that the time Pat fell downstairs and cut his chin was before her mother cut her hand and not after -- things like that.

Then the head nurse gradually forgot Nolan, for she was engaged to marry Burke and had many things to think about and had to give him her off-duty time. It was fully a month and a half after she had last visited the Nolans that Burke spoke to her about them. He had a small car of his own and they were driving out the South Road. Spring was in the air,

"Nell," Burke said, "you remember Nolan, that fellow that got the bump on the head; I want you to help me out; I'm up against a tough question; you've got to tell me what to do. He's not Nolan.

"I told you I was going to look him up, and I did. Nolan's dead; he died in Chicago a year ago."

The head nurse threw back her head and screamed with laughter. She was almost hysterical over it.

"And we giving this man a family already made!" she cried. "Forcing it on him! Oh! I'll die laughing!"

"That's it," said Burke seriously; "that's just it, Nell. That's why I don't know what to do. Now listen. You know that cap he had, and those clothes? I traced them. That M. J. N. was none of his name; it's the initials of a Martin Jerome Newton, at Talavera. And it was eighty-six dollars this guy had when he got the bump on the head; that's the exact money that was stolen from this Martin Jerome Newton the night before this fellow got the bump. This guy is a crook, see? Well --?"

"And he's lost his memory --"

"And he has not lost his memory," said Burke. "Take it from me, Nell, he knows who he is as well as I know my own self."

"I don't believe he does, Tom."

"He remembers all right enough," Burke declared, "but he remembers the police found him with that money and that cap and all too. So it's mighty convenient for him to forget, Nell. It's mighty convenient for him to be Nolan, with a good job, instead of a convict with twenty years in the pen to work out. The only thing that bothers me --"

"I know," she said. "Those fatherless children. Drive back to the North Road, Tom; I haven't seen them for weeks."

"If he's a crook," said Burke when he had turned the car and they were on their way to Enderby's, "he ought to be in the pen, but if he don't remember anything he ain't the same man he was. I can get that. The thing that riles me is to think he may be putting a job over on me; thinking he has us all fooled. If he honest to goodness thinks he is Nolan I'm not so eager to have him go to the pen. So that's the question -- does he think he's Nolan, or does he know he's not Nolan?"

As they neared Enderby's they saw the gardener and Frowzy working in the garden, clearing away last year's dead stuff. Frowzy's wide back was toward them as he went over his work and he had paused a moment to listen to something the gardener was saying to him.

He looked up as he heard a shout, and across the lawn came Pat and Mary and Aileen, just out of school, running toward him, waving report cards in their hands. Aileen tripped and fell, and Frowzy straightened up and started toward her, but she jumped up again and came running and Frowzy brushed his hands together and held out his arms and Pat went into them with a leap, with his arms around Frowzy's neck.

"Drive on, Tom," the head nurse said. "What does it matter who he is -- he's Nolan."