from Success Magazine

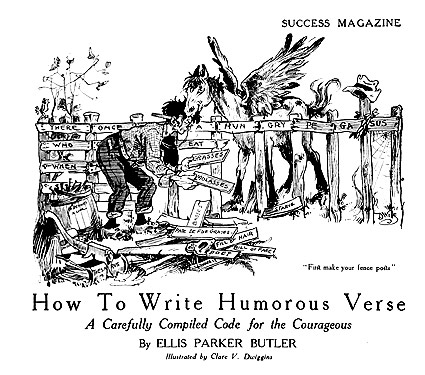

How to Write Humorous Verse

by Ellis Parker Butler

My new book, "How to Write Humorous Verse," having just come from the press and being for sale at all the department stores, where you can get it, of the blonde pompadour at any book counter at $1.08, provided you have $1.08 and she has the book, -- she will tell you she hasn't and will recommend something else, but don't be deceived by substitutes, -- I want to say a few words about the book to correct any misunderstanding regarding it. The report has gotten abroad that I do not know what I am talking about, when I pretend to tell others how to write humorous verse, and that I am a fraud and cheat and never wrote a really humorous verse in my life. I refuse to believe it. Any one who wants to make me believe that will have to prove it to me.

My new book is the fourth of my well-known "How-to" series and is bound the same way, with a swinging lid at each end. The color of the lids is a lovely sky blue, like my other "How-to" books. The other volumes of the series are "How to Write Psalms," "How to Pickle Olives," "How to Catch Trout," and "How to Write 'How-to' Books." I have underway two more entitled "How to Write Dramas" and "How to Cure Hams."

The first chapter of "How to Write Humorous Verse" divides humorous verse into two principal divisions: First, humorous verse that is funny, and, second, humorous verse written by others than myself.

The second chapter begins with the query, "What is the lowest form of humorous verse?" The pun is said to be the lowest form of humor. I boldly announce, in Chapter II., that the Limerick is the first form, or lowest-down form, of humorous verse. I explain what a Limerick is. "A Limerick," I say, "is a poem of five lines, two of which are sawed off, shorter than the others." By this description any one can tell a Limerick who sees one. I advise all beginners to learn to write Limericks first of all, before attempting things like the "Biglow Papers" or "Nothing to Wear." To show how clear my instructions are I quote from the book: --

"We will now proceed to compose a Limerick. To do this the learner would best draw on a blank sheet of paper something like five rows of fence posts, thus: --

| | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |

"By doing this the art is rendered much simpler, for all that is necessary is to write one syllable in each space between the fence posts. It also serves to prevent the enthusiastic beginner from getting the third and fourth lines too long. In the heat of joyous composition the poet is apt to forget to keep these two lines short, and he goes ahead and writes them as long as the others, which makes for him additional work, for he has to go back and cut part of them off afterwards. It is always best to lay out a map of the Limerick first, just as a good cabinetmaker will not begin to make a sofa unless he has his working drawings before him.

"Now we will take a well-known Limerick from the celebrated work, 'Mother Goose,' as a model. We will choose, --

"'There was a fat man of Bombay

Was smoking one sunshiny day

When a bird called a snipe

Flew away with his pipe

Which vexed that fat man of Bombay.'

"This is a very beautiful example of the great heights of soulful humorous inspiration the Limerick can reach, and it is also an example of economy. There is something irresistibly funny in the idea of the stout gentleman smoking in peace in the warm sun and probably half dozing, and then pop! comes the snipe and flies away with his pipe. It was probably a meerschaum, too, and doubtless the snipe dropped it on a stone and smashed it to bits. This Limerick would be absolutely perfect if the author had only managed to let the snipe drop the pipe. It would have added tremendously to the fun, -- and that is what humor is, just fun. But we can pardon the author. It is better to omit the fun entirely from a Limerick than to crowd too much matter into it. Always remember that a Limerick is not a sausage. It should not be stuffed too full. Leave something for the imagination.

"As to the economy of which I spoke, please notice that both the first line and the last line end in the same word, -- Bombay. The author might have used an entirely new rhyme in the last line, but there is no labor so terrific as thinking out rhymes, and I compute that by thus saving one rhyme in each Limerick he saved enough brainpower in five Limericks to make a sixth Limerick, and thus the world was the gainer.

"Now, notice another thing about this Limerick I have given as a model. The last word of the first line is the name of a place. Bombay is a town in Arabia, I believe. If it isn't in Arabia, it is over in that section somewhere, and it doesn't matter where it is, for the important point is that in nearly all Limericks the first lines end in the names of places. Only very advanced Limerickists end the first line in any other way, and they are men of exceptionally fine minds.

"The reason for choosing a place name is that it suggests the idea for the Limerick. Every writer knows that ideas are hard to think of when it comes time to write. Many persons who might have been our greatest poets, outshining Shakespeare, were obliged to take to some other business, merely because when they sat down to write they could not think of an idea. This is one of the saddest things in the history of poetry. The other saddest thing is that there is no rhyme for 'chimney.' Whenever you want to say 'chimney' at the end of a line in poetry, you have to say smokestack. Many a beautiful heroine who would have lived in a mansion with a chimney has therefore been obliged to live in a 'shack' with a 'smokestack,' because they rhyme.

"But we will now go back to our fence posts. We have found that Rule I. is 'First make your fence posts.' Rule II. is 'Take some place.'

"There are plenty of places to take. The atlas is full of them, and we may take nearly any one we want. A few -- a very few -- have been taken already. The Japanese took Port Arthur, and the Dutch took Holland and I knew a Kentucky gentleman who took Rye; but most of the names in the atlas are yours to choose. We will take Moline, because I used to know a girl there, and it is a very tender compliment to choose the name of a place where a friend lives.

"We will now write 'Mo' in the space next to the end in our top row of fence posts, and 'line' in the last space, and our poem is really begun.

"Next we pick a rhyme for 'Moline.' Bean, seen, green, wean, keen, -- there are so many that we need not economize. We will choose two, -- say 'machine' and 'clean.' It doesn't matter what the words are, so long as they rhyme. We write these between the posts at the end of the second and fifth lines.

"Now we need two more rhymes to tack on the third and fourth, or, as professionals call them, the 'bunty' lines. We can take any two words in the rhyming dictionary, -- 'lake' and 'shake,' or 'trance' and 'prance,' or any others. Suppose we take 'why' and 'buy.' We write them in the last lap of fence in the third and fourth lines. Now our lines look like this: --

| | | | | | | Mo | line |

| | | | | | | ma | chine |

| | | | | why |

| | | | | buy |

| | | | | | | | clean |

"The rest is comparatively easy. We can put aside the heavy atlas and the troublesome rhyming dictionary. All the rest we will find in our own heads.

"We begin by writing 'There was a' in the first three gaps in the fence, and what 'there was' depends on what we want it to be. Perhaps we will say 'young man,' and, behold, we have the first line of posts filled up: --

"'| There | was | a | young | man | of | Mo | line |'

"Now our last rhyme in the Limerick is 'clean' and the second is 'machine.' The only kind of machine that has anything to do with 'clean' is a washing machine, so we put 'wash' and 'ing' before the word 'machine.' What, then, did the young man of Moline do to or with or about a washing machine? He could only get it in one of four ways; make it, steal it, borrow it, or purchase it. The most natural way would be to purchase it. Probably he did that. If so, we find we have: --

| There | was | a | young | man | of | Mo | line |

| Who | pur | chased | a | wash | ing | ma | chine |

| | | | | why |

| | | | | buy |

| | | | | | | | clean |

"Now, my dear student, you begin to see the humor sticking out of our Limerick. Here we have the incongruous, which is the basis of all humor. A young man buying a washing machine! Silly goose, wasn't he? But he must have had a reason for buying a washing machine. That word 'why' in our third line seems to ask a question, and the 'clean' in the last line partly answers it. He wanted to keep something clean. Fill out the fence-posts gap in the last line!

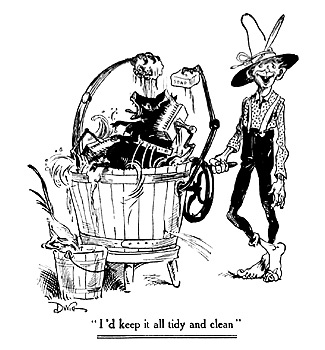

"'I'll keep it,' says the young man, 'all tidy and clean.'

| "I'll | keep | it | all | ti | dy | and | clean." |

"That is the answer, but it must answer a question. We go back to the third line, where 'why' is waiting for us as patiently as a pig on ice. What have we so far?

| There | was | a | young | man | of | Mo | line |

| Who | pur | chased | a | wash | ing | ma | chine |

| | | | | why |

| | | | | buy |

| "I'll | keep | it | all | ti | dy | and | clean." |

"There is only one thing we can write in that third line. It suggests itself. We don't have to think.

| He | said, | when | asked | why, |

That is the only logical thing to put in that line, and we must put it in, and then we have: --

| There | was | a | young | man | of | Mo | line |

| Who | pur | chased | a | wash | ing | ma | chine |

| He | said, | when | asked | why, |

| | | | | buy |

| "I'll | keep | it | all | ti | dy | and | clean." |

"Excellent! All our Limerick needs is the connecting line, and all poets know that the last and connecting line is the easiest to supply. Here we have a young man with a washing machine and we have our word 'buy.' What could he buy that needed to be kept 'tidy and clean?' What needs most to be kept 'tidy and clean?' What is the most untidy and unclean thing? A pig!

"'If I should buy a pig,' says the young man.

"Shunt the words around so that 'buy' will come where it belongs, and we shall have: --

"'If a pig I should buy.'

"We fit that to our fourth line of fence posts, and -- but what's this? It doesn't fit inside the six posts of the fourth line! See, --

| "If | a | pig | I | should | buy |

"Do not despair, gentle student! I will now give you the third and greatest rule of poetry writing: --

"Rule III. -- If the words do not fit exactly between the posts, put in more posts.

"This is a rule I invented myself, and I have found it of the greatest possible use. This one rule alone is worth the price of this book. It makes humorous-verse writing an actual pleasure, and takes away the deadly grind that has filled so many of our humorous-verse writers with cark and care and driven them to writing pathos in prose.

"Thus we have learned, quickly and easily, the first lesson, 'How to write Limericks,' and our finished product is neat and stylish. Rub out the posts, spatter in a few punctuations, and, warm, glowing, and palpitating, we have the Limerick we have created, --

"'There was a young man of Moline

Who purchased a washing machine;

He said, when asked why,

"If a pig I should buy,

I'd keep it all tidy and clean."'"