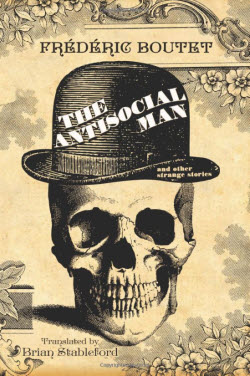

Review by Glenn Russell

Singular tales told in rich,

opulent language, January 12, 2014

Perhaps it would be appropriate

to have this book of Frederic Boutet's rococo tales fitted with a fine

cover of black leather inlaid with golden arabesques, and then, after

partaking of a tincture of opium or wine, book in tremulous hand, surrounded

by odiferous flowers and pungent perfumes, in solitude, at midnight, by

the light of a solitary candle, take a seat in a plush chair. With these

modest preparations - the decorated cover, lavish ambience and one's inner

hypersensitive state - a reader will begin to match the author's ornate

sentences and baroque storytelling.

Indeed, if you have a taste

for the fantastic, for gothic horror, for weird characters and arcane

landscapes described in rich, opulent language, for a book that could

be sub-titled `Deadly Beauty', then this collection translated and introduced

by Brian Stableford and published by Borgo Press might become one of your

very favorites. By way of specific examples, here are a few quotes and

my comments on three of the thirteen tales:

The Veritable Victory

A pale-faced, black-bearded visitor removes his top hat and cloak and

is lead to a room where a young woman of great beauty, dead to all appearances,

lies on an ivory bed with lace pillows and satin sheets. We read, "He

thought: What does tomorrow matter? She is beautiful tonight; she is all

mine; and I shall love her until I vanquish death!" And then we read,

"He possessed her in a voluptuous delirium multiplied tenfold by

opium." We know right from the outset this is a scene that has been

repeated many time before: the visitor is lead into the house by a horror-struck

old housekeeper and the woman lies on the bed as if dead. But then one

night there is an unexpected change. The author writes, "But he exhausted

himself in vain in gluing his lips to the pale mouth; she did not part

her own any more. In vain, he caressed the voluptuous body passionately,

but she did not quiver and her arms did not return the embrace. The translucent

eyelids remained closed over the large blue eyes, the little feet were

icy, the limbs became ever colder, ever heaver." One senses Boutet

coated every sentence of his sumptuous, extravagant tale with overpowering

cologne and death.

The Idol

Lost in a forest, a mounted traveler by the name of Jean Falmor encounters

ugly, stinking creatures gnawing on roots. He then comes upon Marestote,

a holy black monk, a monk who tells Falmor how the brutish half-men he

now sees crawling around the fires had their souls devoured by a fatal

power: Woman. Confidence in his holiness and Christian mission, Marestote

invites the traveler to join him in his confrontation with his evil enemy.

At the point in the story when the black monk challenges the Woman, Boutet

describes what these two men see when the Woman displays her miraculous

naked beauty: "The whiteness of her skin is mat and polished, with

a gilded roseate translucency. Above her arched feet, resting on a swans-down

carpet, the slimness of her ankles elongates and folds back lazily. Then,

there is the gracious grasp of the knee and the voluptuous plentitude

of thighs; the skin is as delicate as the most adorable silk, seemingly

warm and perfumed, and the delight of its touch must be superior to any

other." This is but one paragraph of description; Boutet goes on

to further describe the Woman (author's capitalization) in equally florid

language in five more paragraphs. Not only does this tale contain a most

exquisite description of female beauty but also will prompt us to reflect

on our philosophical and theological presuppositions.

The Antisocial Man of the

Qual Bois-L'encre

This Boutet story is decidedly unlike the others in the collection in

a couple of ways - first, at 72 pages, it is a much longer piece; and,

second, the story is a mad-cap cross between two forms, what would come

to be known in the 20th century as 1) South American magical realism,

and 2) Soviet absurdist fiction. To underscore this point, the story's

characters provide reports not only on the Antisocial Man, a recluse isolating

himself in a top floor apartment, but also creatures sharing the Antisocial

Man's living space, including a baboon, brown bear, anti-bear, hippopotamus,

kangaroo, goat, boa constrictor, armadillo and a bearded vulture. And

what more detail do we have on the Antisocial Man? Here is a description

from a bailiff's notebook: "The Antisocial Man, as I've said, is

not mad. At the very moment when I am writing these lines I can see him

through the foliage, a short distance away. He is sitting on the edge

of the spring. He is thin, beardless, muscular, sardonic and calm. He

is smoking his pipe. His clothing is simple. He rarely speaks. Sometimes

he reads books. At his feet is his favorite goat: a very young, very pretty,

very affectionate and very capricious goat, which never leaves him for

long and for which he appears to have, doubtless in imitation of Robinson

Crusoe, an excessive tenderness." You may ask: how can an apartment

have foliage and a spring? Again, this is a work of sheer imaginative

fancy, an occasion for our singular author to stretch his creative powers

and literary inventiveness.

|