from Century Magazine

The Last Conversion of Sally-in-the-Hollow

by Ellis Parker Butler

In her early days of grass-widowhood there was never a revival that came to Zeekville and departed leaving Sally-in-the-Hollow unconverted. Her conversions, although violent, were not notably permanent. While they lasted they were full of woe and agony, but, as Sally herself admitted, they did not "take." For a few Sundays and Thursdays after the revival she would attend church and prayer-meeting with savage vim; then, as her mind slipped back into the daily routine care of her children, and the necessity of keeping her wash-tub full pressed upon her, she would slide away, and slide away, until she was completely and joyously backslidden.

"Ah swear Ah dunno whut the matter wif me," she admitted to Mrs. Dugan, the only other dweller in the Hollow. "Ah jus' done give up hope of eveh stayin' converted. Ah do wish Ah been born Cath'lic, like you-all, Mis' Dugan, foh yo' 'ligion do seem to stick right to you; but my 'ligion runs off'n me lak water oft'n a duck's back. Ah've been urged on to the mourner's-bench twenty-two -- no, twenty-three times, an' each time Ah said, 'Sally, dis time yo' been save' foh good'; an' next thing Ah know Ah 'm jus' as backslid' as ever. Ah have all dose yere pangs an' agonies fer nuffin'. So Ah jus' done mek up my mind t' stay backslid', yassum."

Mrs. Dugan, to whom these soul crises of her colored neighbor were an old tale, did nothing but sigh sympathetically.

"Co'se," said Sally, "Ah reckon you-all don' think it meks much diff'rence whuther Ah stay slid' or backslid'. But 't ain' as if 't was 'come easy, go easy'

with me. When Ah get took with 'ligion. Ah get took mighty pow'ful, an' 't ain' nothin' but agonize, agonize, agonize day in an' day out. Yassum, seem lak my soul jus' get caught in the pinchers of de Lawd, an' Satan grab de udder end with he pitchfork, an' it 's twist, twist, till Ah 'clare my soul 'most twist clean in two."

"An' will ye listen t' that now!" said Mrs. Dugan, sympathetically.

"Ah jus' mek up my mind Ah ain' gwine to tek one step t'ord dis yere revival whut's been start' up in town," said Sally, positively. "Ah got so much washin' on hand Ah dassn't tek de time. When Ah get in a soul-agony Ah forgit all about washin' an' ironin', an' Ah get iron-rust all over de white shirt-fronts, an' Ah don't get de grass stains outen de clothes, an' Ah ain' fit to be call' no decent washwoman at all. The las' time Ah been converted Ah lost three mighty good-payin' customers, an' when de wash comes home lookin' lak de dickens, de white folks don't tek soul-agony for 'sense. No 'm: dey jus' say, 'Sally, you can agonize all you feel lak, but Ah reckon Ah'll get my wash done elsewheers.'"

So this time Sally kept her face resolutely away from the path that led out of the Hollow toward the church and Zeekville. She clung to her washboard and wringer as to opiates, and she slammed her irons down hard on the ironing board to deaden the call of her conscience. From time to time she had visions of the crowded, ill-ventilated church, where super-excited nerves burst into hysterical cries and moans, and she could see as clearly as if she were present the shouting congregation as another convert was aided, sobbing, to the "bench." By the third day she was so nervous that her hands trembled. She was like a drunkard who sees a bottle, but who has sworn never to touch drink again.

But this time Sally was firm in her resolve to stay away from the revival meetings. She had had a hard time of her life, "bootlegging" whisky on the sly until she was twenty-five, and then marrying a "no 'count" colored man. Upon her marriage with him she had found that bootlegging did not serve to support them both, and she had taken to washing. The constantly increasing family of small brown children had fastened her firmly to this more respectable calling. It was no loss, but rather a relief, when her worthless husband wandered away, never to appear in the Hollow again.

On Wednesday afternoon of the second week of the revival Sally was in the condition of an inveterate smoker the second day after giving up tobacco. She was cross and fidgety, and she could not keep her mind on her ironing, and when she heard a loud knocking on her front door, she welcomed it. Even a visit from the stove man, seeking to collect an installment, would have been a relief. She needed diversion.

Sally's house had never been painted; but one, years before, she had whitewashed it and a few patches of yellowed lime still clung under the eaves. Otherwise the house had weathered into a soft gray, into which the dust had settled, and the tall, dusty weeds about it were almost as high as the house. Her front door was seldom used. It opened outward, and it sagged on the rusty hinges. Sally unhooked the staple, and kicked the base of the door with her large, carpet-slippered foot, but the door refused to yield. She placed one strong shoulder against the upper part of the door and pushed. The lower part of the door still stuck fast, but the upper part gave open an inch or so, and her visitor, eager to aid, put his brown fingers in the crack. Then Sally stood back to give the door another kick.

Instantly the four brown fingers were clasped between the door and the casing, and her visitor howled. The sharp edge of the door caught him just below the first knuckles with a grip like that of a steel trap.

"Lemme out! Lemme out!" yelled the man.

Sally stared at the fingers. Something in their appearance reminded her of her vagrant husband, and her eyes blazed.

"Let yo' out!" she cried. "Yo' ain' in yet! Who is you? Is you my husban'?"

"No, Ah ain'," cried the man. "Ah ain' nobody's husban'. Lemme out!"

It was not her husband's voice, and with a mighty kick, followed by a battering-ram blow from her shoulder, Sally managed to move the door a foot or so.

She pushed her head through this opening and surveyed her visitor.

"'Scuse me, sah," she said contritely. "Ah'm so sorry Ah pinched yo' hand. 'T was mighty foolish fo' yo' to put dem fingers in dat crack. Yo' might have been mah husban', an' den Ah would jus' have lef' yo' holler there."

"De do' did cert'ly pinch mah fingers perniciously, ma'am," said the man, politely; "but Ah ain' yo' husban'. Ah ain' so lucky."

"How long yo' been sellin' books?" asked Sally, who thought she recognized in his words the preliminary complimentary palaver of the book-agent kind, and wished to let him understand that she was possessed of insight. The man did indeed look like a book-agent. He was tall and dark, and he wore black clothes and a hat that had once been a silk hat. Now he was seeded from head to foot with dust and pollen from the forest of weeds that edged and encroached upon the narrow path that led to the Hollow. That he carried no book in his hand meant nothing, for Sally was acquainted with the wiles of book-agents, and knew that, once seated in the house, the book could be made to appear from the inside of the hat, from the capacious skirt of the black coat, or even from a hiding-place between the shoulders. But, willing as she was to receive entertainment, Sally would not invite her visitor into the house on false pretenses.

"Ah don' want to buy no books today," she said.

"An' Ah don' want to sell yo' none, ma'am," said the visitor. "Ah jus' come down to have a talk -- jus' a little friend-like talk --"

"Then if yo' jus' turn sideways-like, an' squeege a little," said Sally, "Ah'll be glad to welcome yo' into mah house. Ah can't seem to 'nipulate dat door no more outwards than what it is."

"An' Ah don' requiah no mo' room," said the man. "Ah'll get in, if yo' jus' kindly remove yo' head outen the crack."

Sally backed away, and her visitor edged into the crack. He was a close fit.

"Mah name," he said, as he squeezed through, "is Mistah Jones."

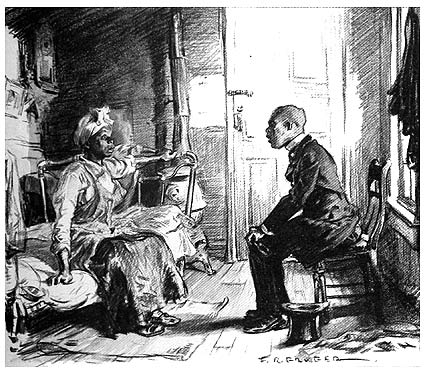

Once in the house, he took the chair that Sally motioned to. It was the only chair in the room, which was both bedroom and parlor, but not exceedingly parlor. It had a few scraps of soiled and worn matting on the floor, and the one iron bed had been gilded as far as the gold paint had held out. Otherwise the room was furnished with several pallets, laid along the wall -- the beds of the numerous children. Sally seated herself on the edge of the iron bed. She leaned her elbows on her knees and sighed contentedly. The next move would be for the man in the white tie and black-garb to say, "Now, Ah ain' sellin' books, but Ah got a work here whut Ah'm introducin' to a few high-toned culled famblies --" But be said nothing of the kind.

He laid his hat carefully on the floor at his side, placed the tips of the fingers of his two hands carefully together, and smiled reassuringly at Sally.

"Sistah," he asked, "has yo' ever took consideration of the fac' dat we all mus' die?"

Instantly Sally sat upright. The placid calm of her face gave place to a harsh, defiant frown.

"Yas, Ah has," she declared. "An' furdermo', it ain' goin' do you no mite of good t' call dat fac' to mah mind. Ah know all 'bout dat boun'-to-die business, an' Ah been converted twenty-three times; an' when Ah got to die, Ah got to, an' Ah ain' gwine care two shucks whut happens. No, sah. Ah know whut yo' here fo', an' it ain' gwine do yo' no good to waste yo' conversation on me. My mind's made up."

But Mr. Jones only smiled a pitying smile.

"Ah hear dat," he said, "from one week till the nex'. Ah's got so 'customed to dose words Ah jus' don' pay no 'tention to dem at all. Sistah Sally, Ah say unto yo' -- yo' gwine die. Yo' gwine be cut down like de grass some day. No mistake 'bout dat. We all gwine be cut right spang down."

"All right," said Sally, stubbornly. "Ah jus' got to take my chances 'bout dat. 'T ain' no use talkin'. It mighty kind on yo' to come down into de Holler for to preachify to me, but Ah jus' can't afford to hearken to yo'. Ah got all my chillun to support --"

Mr. Jones nodded his head, and tapped the tips of his fingers together lightly.

"Sistah Sally," he said, "yo' do well to think 'bout yo' chillun. Ah ask yo' to think 'bout them specially -- specially. Don't it wrack yo' heart to think of goin' off an' leavin' dem little chillun oncared fo' an' onprotected? Ain't yo' more high dan the beastes of de field? Ain't yo' gwine be more to dem little chillun dan de fowls of the air? Now, ain't yo'?"

Sally rocked herself to and fro. Through her veins she felt the quiver of the coming exaltation, but she tried to fight it back.

"Ah come to yo'," said the man, leaning forward and clapping his hands, "fo' to 'peal to yo' on behalf of dem chillun! Ah want dem chillun to think of deir ma in glad respect when she's gone off'n de yearth. Yassum. Ah want to save yo' from remorse dat day when yo' lie flat on yo' back an' the Angel hovers over yo'. Ah want yo' to know an feel Sistah Sally, 'bout de mighty guardian whut Ah repersent. Ah want to tell yo' 'bout how dat mighty guardian watches ovah de little chillun an' pertecks 'em. Today yo' may consider yo' are all-fired well, but tomorrow --"

Sally rocked backward and forward, and the tears gathered in her eyes.

"Oh, yes! Oh, yes!" she cried. "Ah know! Ah know!"

The man in black struck his hands sharply together.

"Now yo' shoutin'!" he cried. "Now yo' on de right track! Now yo' begin' to see de light! Now yo' considerin' yo' poor little chillun in the depths of yo' heart! Sistah, I ain't heah to plague yo'. I ain't come down unto the Holler to force yo' to do yo' duty. No, 'deed! Ah got my work to do, an' Ah can't 'low mahself to be put off jus' because yo' ain't acquainted with whut Ah mean. Ah ain' workin' in dish yere field 'cause Ah gets money fo' it. No, 'deed! Ah been felt a call, Sistah. Ah ain't nothin' but a humble worker in de big field. Ah on'y repersent de mighty power whut sends me forth. Ah ain't talkin' fo' mahself; Ah'm talkin' fo' yo' peace of mind; Ah'm talkin' fo' de good of yo' little chillun."

Sally raised her hands in the air and brought them down on her knees.

"Glory!" she shouted. "Glory!"

Then suddenly she tried to control herself.

"Dat all right," she said. "Dat all right. Ah see yo' gwine get me if yo' want to. But 't ain' no use, brother, 't ain' no use. Ah been convinced before, an' Ah been took in before, an' 't ain' no use. Ah gwine drop right out ag'in, lak Ah always do. 'T ain' nuffin' to work me all up, an' get me convinced; but byme-by Ah forgets, an' Ah slides right out ag'in! Ah forgets! Ah forgets!"

Brother Jones brought his fist down on his knee.

"An' Ah tell yo', Sistah Sally," he said fiercely, "dis time Ah ain' gwine let yo' forget. No 'm! Ah gwine watch over yo', an' mek yo' way easy. Ah gwine come see yo' every blessed week! Yo' can't forget! Yo' can't drop out!"

"'T ain' no use," said Sally, wiping her eyes. "Ah knows how 't will be. Yo' gwine get me in, an' harrow me all up, an' den yo' gwine away from Zeekville, an' Ah gwine be right back spang where Ah was."

"No 'm," said Mr. Jones, positively. "No 'm, Sistah Sally. Da' 's de old way, but de new day has come. Da' 's not my way. Ah been given dis field, an' Ah stay right here. Yassum, Sistah Sally. 'T ain' 'nough fo' me to get yo' to come in; Ah keeps yo' in. Ah knocks on yo' do' every Friday mornin', an' Ah says, 'Sistah Sally --'"

"Wha' 's dat?" asked Sally. "Yo' gwine come down unto dis Holler yevery week?"

"Ah certainly am," said Mr. Jones. "Ah gwine do dat thing. Ah ain' gwine let yo' forget. Ah gwine say, 'Sistah Sally, 'member yo' little chillun!'"

"Oh, glory! glory!" cried Sally.

"Ah gwine have mah place uptown," said Mr. Jones, enthusiastically, "an' if yo' wants, yo' can come unto me; an' if yo' don't, Ah'll come unto yo'."

"Oh, glory! glory!" cried Sally.

"Ah mek de way easy," said Mr. Jones. "Are yo' ready to give me yo' name, Sistah Sally? Ah yo' ready to --"

"Ah's ready!" cried Sally, clapping her hands. "Hallelujah! Ah's ready! Ah's convinced! Ah 'm done converted!"

The visitor took a large envelope from his pocket, and from the envelope he took a paper. From another pocket he drew a pen.

"Sistah," he said, "Ah got to ask yo' whut is yo' name."

"Sally Johnson," cried Sally. "An' Ah want to jine de Baptis' church."

"Yo' gwine jine any church whut yo' wants to," said Mr. Jones. "Ah don't have nothin' to do wi' dat. How old yo' is?"

"Fifty-fo", an' Ah done been baptized. Ah'm safe in the church!" cried Sally, joyfully.

Mr. Jones folded the paper and tucked it into his pocket again. He carefully placed the cap on his pen, and put it in his pocket. Then he rose.

"Mis' Johnson," he said, "Ah got to 'gratulate yo' on dish-yer act what yo' done consummated. Yo' ain' gwine nebber regret it."

"No. Glory! Ah gwine be so happy! Ah gwine be like new!"

"Yo' is indeed," said Mr. Jones, taking his hat and rising. Sally stared at him.

"Ain' yo' gwine to -- ain' yo' gwine to -- to lead in pra'r?" she asked wistfully.

Mr. Jones placed his head on one side and looked at Sally, doubtfully.

"Well, co'se," he said, "Ah can lead in pra'r if yo' want me to so do, but it ain' usual. No 'm; it ain' usual. Ef yo' was to get a reg'lar preacher, 't might be more seemly. Ef Ah was a revival preacher --"

Sally jumped from the bed and stood facing him with angry eyes.

"Wha' 's dat?" she cried. "Wha' 's dat? Ain' yo' no revival preacher?"

"Why, no 'm," said Mr. Jones, with a puzzled frown. "Why, no 'm."

"Ain' yo' done converted me?" cried Sally, angrily. "Ain' yo' come down yere to bring me unto repentance?"

"Why, no 'm," said Mr. Jones, vacantly.

Sally stared at him silently for a full minute. When she spoke, she snapped out her words like the clicking of steel.

"Look yere, man," she said, "ef yo' ain', what has yo' done? Ef Ah ain' done been converted, what has Ah been an' done?"

"Why -- why --" said Mr. Jones, feebly, "yo' done tuck out a life 'surance policy in de Colored Gyardian 'Dustrial Life 'Surance Comp'ny."

"Fo' de land's sake!" exclaimed Sally.